ARTISTS BEHAVING BADLY

WARNING — THIS ARTICLE COULD BE TRIGGERING

Eric Gill

WHEN BIOGRAPHY BLINKS

This started with Fiona MacCarthy’s biography of Eric Gill. The shock wasn’t only Gill—incest with his sisters and sexual abuse of his teenage daughters—but the tone. In a Guardian essay about researching his diaries, McCarthy writes that the entries were “certainly shocking” but “somehow… came as a relief to me.” The Apollo tribute praised her “calm,” noting that while none of the acts was “especially horrifying,” their occurrence in a “pious household” was merely “disconcerting.” Relief? Disconcerting? That chill in the prose is what set me off. Why does the narrative go soft precisely where it should turn hard?

For readers in the U.S.: Eric Gill (1882–1940) was a British sculptor, letterer, and type designer whose fonts—Gill Sans and Perpetua—still sit on countless computers.

Gill’s abuses aren’t rumor. MacCarthy published them from his diaries—sisters Angela and Gladys; daughters Betty and Petra—and has reiterated the details since (see the Observer timeline).

Otto Muehl

SEX, MINORS, AND THE ART-WORLD STOMACH FOR IT

At one end of the spectrum is Otto Muehl, who wasn’t merely “problematic”—he was convicted in 1991 of sexual offenses with minors tied to his Friedrichshof commune (see also an art-press overview).

A particularly disturbing Balthus, The Guitar Lesson.

With Balthus, the argument lives inside the pictures. In 2017 the Met kept Thérèse Dreaming on view despite a petition arguing the work “romanticizes the sexualization of a child.” We can argue labels all day; we can’t pretend the controversy isn’t now part of how the painting reads (see also the museum decision coverage).

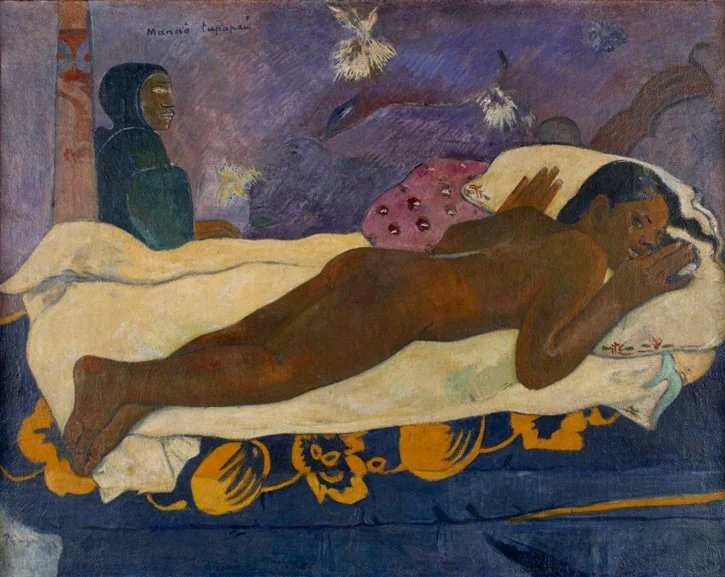

Gauguin

And Paul Gauguin? Museums now acknowledge that Teha’amana—the subject of his 1893 portrait—was 13 in his own account. “Muse” was often a euphemism for power.

Benvenuto Cellini’s Perseus

MURDER, VENDETTA, SWAGGER

Benvenuto Cellini killed his rival Pompeo during the 1534 turmoil in Rome and was later absolved by Pope Paul III; he also hunted down and killed an arquebusier (a soldier with a firing arm) after his brother’s death. Strip away the autobiography’s swagger and the homicides remain.

Caravaggio, David with the Head of Goliath

Caravaggio knifed Ranuccio Tomassoni after a duel in 1606 and fled under a capital sentence.

Eadweard Muybridge, Fencing

Even photography gets a case study: Eadweard Muybridge shot his wife’s lover in 1874, and a California jury returned not guilty on “justifiable homicide,” against the judge’s instruction—an eyebrow-raising verdict even then (see the case note).

NAZI, MYTHS, AND THE POSTWAR RINSE CYCLE

Emil Nolde, Marsh Landscape Evening

For decades, Emil Nolde was cast mainly as a victim of “Degenerate Art.” A 2019 exhibition in Berlin documented his Party loyalty and antisemitic writings alongside his persecution—myth, meet archives (see also the museum’s release).

Arno Breker, The Game

Arno Breker wasn’t coy: Hitler’s favored sculptor, made official state sculptor, and placed on the Gottbegnadeten (“divinely gifted”) list in 1944 (for an overview, see this Guardian piece).

ALLEGATIONS WON’T REST

Installation view of Carl Andre: Sculpture as Place, 1958–2010, April 2–July 24, 2017 at The Geffen Contemporary at MOCA, courtesy of The Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles, photo by Brian Forrest

Carl Andre was acquitted in a 1988 bench trial in the death of Ana Mendieta—that’s the legal fact. The cultural fact is persistent protest and reappraisal (for one entry point, try this interview/podcast at The Art Newspaper).

Chuck Close, detail

Chuck Close faced multiple allegations in 2017; the National Gallery of Art canceled a planned 2018 show. He apologized for making people uncomfortable, denied harassment, and later disclosed frontotemporal dementia—context, not exoneration.

Having been part of the New York art world in the 1970s, I doubt Close’s behavior was unique or even the worst. Sexual harassment, sexual exploitation, emotional abuse, and quiet efforts to derail women’s careers felt like background noise. This is not an excuse. It was a battlefield, and many women carried the scars forward.

ANTISEMITISM AND THE DRYFUS FAULT LINE

Dégas

The Dreyfus Affair split the Impressionists. Degas moved hard anti-Dreyfus—contemporaries, including Pissarro, called him a “ferocious anti-Semite,” a reading traced through his press diet and broken friendships (see Tablet and this survey that builds on Linda Nochlin’s work, Creating the Modern). Renoir is messier but hardly neutral; letters and accounts around exhibitions show both anti-Dreyfus positions and antisemitic digs, even as he had cordial ties to some Jewish patrons (see Shapell).

PICASSO, BRIEFLY

Marie-Thérèse Walter and Picasso

In 1927, Picasso—45 and married—began a secret relationship with Marie-Thérèse Walter, 17. Françoise Gilot’s memoir and later interviews describe a pattern of coercive control and abuse; museums and critics increasingly foreground that history when they present the work (see this obituary).

THE CHARLOTTE SALOMON SHOCK

Charlotte Solomon

Not a “monster-artist,” but a contradictory life: Charlotte Salomon left a 35-page letter describing poisoning her abusive grandfather in 1942—many scholars read it as a confession, others as a hybrid testimony aligned with Life? or Theatre?. Either way, it reframes the work’s proximity to family suicide and wartime terror.

WHERE I LAND (for now)

I don’t want euphemism. I don’t want erasure. I can acknowledge unforgivable acts and still argue the work belongs in public, framed honestly. I don’t want the truth whitewashed, and I don’t want the art erased. The real discipline is holding contradictory facts in your head without sanding them down, letting the discomfort do its work.