THE LINEAGE OF EXPERIMENT: From the Bauhaus to Bennington College to Woodstock Country School

I didn’t realize it at the time, but the schools I attended — Woodstock Country School and later Bennington College — were direct descendants of the Bauhaus experiment. Each believed that art was not a subject but a way of understanding the world. The lineage that ran from Weimar to North Carolina to Vermont shaped not only my education but the way I’ve made art ever since.

Bauhaus Architecture, Dessau, Germany

The Bauhaus — Art as Life

When Walter Gropius founded the Bauhaus in 1919, he imagined a school that would dissolve the boundaries between craft, design, and fine art. Students built furniture, designed typefaces, choreographed performances, and studied color, form, and geometry as universal languages. Josef and Anni Albers, Paul Klee, and Wassily Kandinsky treated art as a social and moral practice, not a luxury. The workshops were laboratories of communal making.

When the Nazis closed the school in 1933, many of its teachers emigrated. The Alberses landed in North Carolina, where they planted the seed of the Bauhaus in new soil.

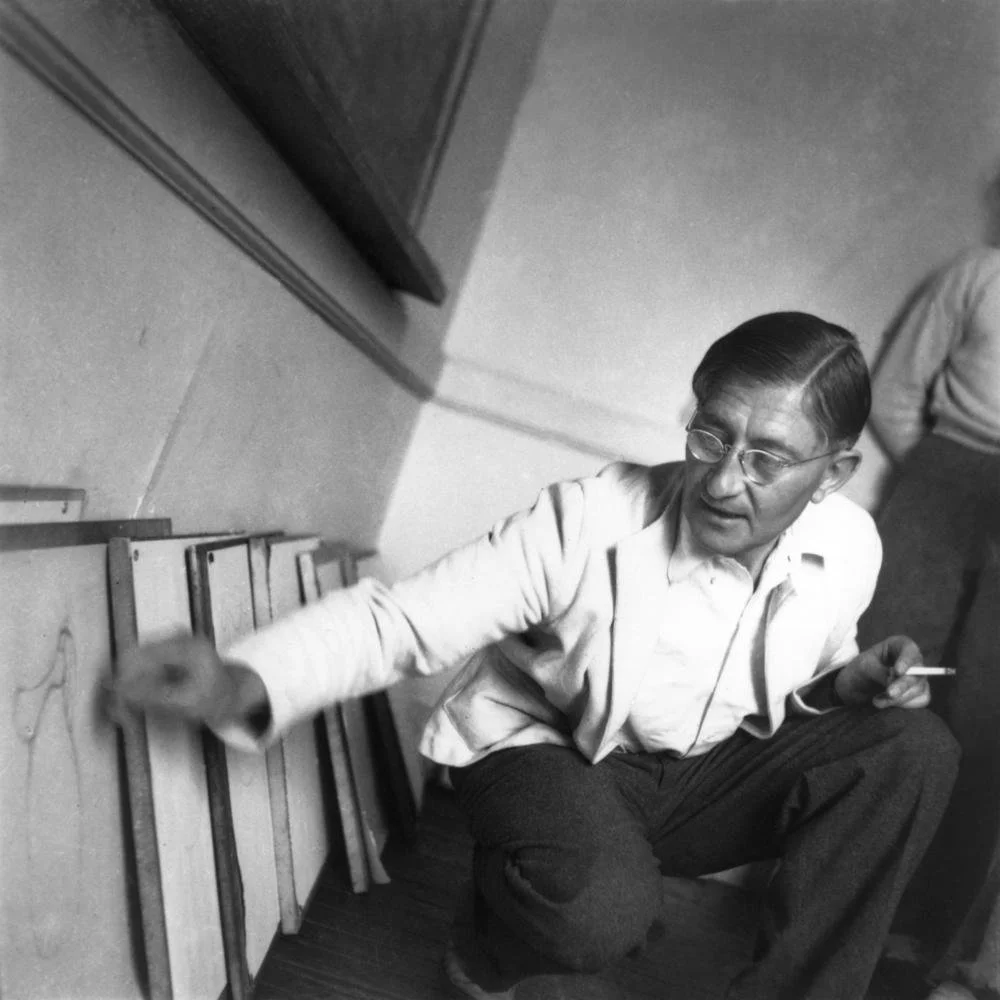

Joseph Albers at Black Mountain College

Black Mountain College — The American Transplant

Black Mountain College opened that same year, founded by John Andrew Rice and others who sought to revamp higher education by integrating the arts and community. Josef and Anni Albers brought the Bauhaus philosophy with them, stripped of ideology but rich with its spirit: learning by doing. Students built their dorms, made their furniture, cooked, cleaned, and studied color with the same intensity they applied to philosophy and poetry.

It became a crucible of twentieth-century art. John Cage, Merce Cunningham, Robert Rauschenberg, Cy Twombly, and Ken Noland all passed through its doors. The boundaries between art forms dissolved — dance informed painting, poetry shaped performance, architecture became social sculpture. Collaboration was not a teaching method; it was the curriculum.

Black Mountain’s experiment proved that education could be both rigorous and humane, an act of generosity where knowledge was shared laterally, not handed down.

Dance@Bennington presents a Contact Improvisation Jam in honor of the Legacy and Passing of Steve Paxton and Nancy Stark Smith

Bennington College — The Northern Counterpart

Bennington College, founded in Vermont just a year earlier in 1932, shared those ideals even if its form was more structured. Influenced by John Dewey’s progressive philosophy, Bennington placed equal value on thinking and making. Learning was experiential and self-directed; art was treated as a legitimate form of inquiry.

At Bennington I studied contact improvisation with Steve Paxton and danced with Trisha Brown through the Whitney Museum Independent Study Program, the one summer it took place in New Mexico. Those experiences shaped how I understood collaboration: not as cooperation for its own sake, but as a form of trust, a way of feeling your way through uncertainty with others. It was the body’s version of the Bauhaus ideal.

Bennington became a magnet for artists and thinkers: Martha Graham in dance, Paul Feeley and Tony Smith in art, Clement Greenberg in criticism. What united them was an atmosphere of disciplined experiment, an understanding that risk was the only route to discovery.

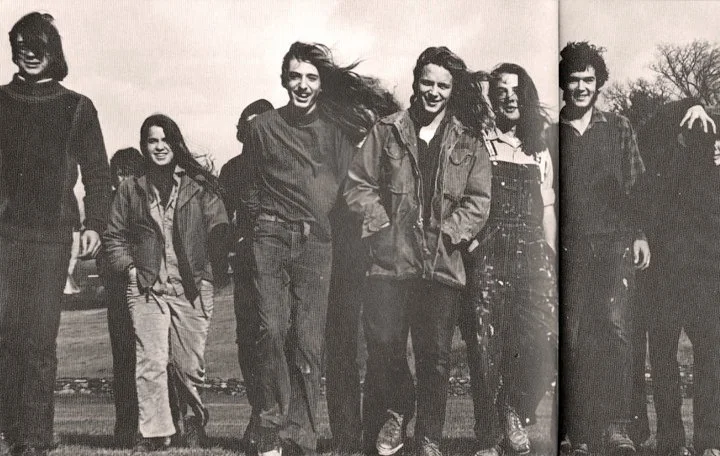

Some of the students at Woodstock Country School when I attended.

Woodstock Country School — The Rural Continuum

After Black Mountain came Vermont’s own progressive experiment, the Woodstock Country School, founded in 1945 by David Welles Bailey, a Black Mountain alumnus. Modeled explicitly on his alma mater, it was a coeducational boarding school where students learned by doing, tending gardens, cooking meals, cleaning dorms, and studying the arts as integral to daily life.

At Woodstock, I studied with a practicing artist, John Semple, and with the daughter of the pioneering documentarian Robert J. Flaherty. Both treated art not as an abstraction but as work, something you practiced, failed at, and returned to. It was an education grounded in presence and daily making, where each act carried weight. If Black Mountain was the American Bauhaus, Woodstock was its rural continuation, smaller, more intimate, but animated by the same faith in experience and collaboration.

My Bonnard Apartment

The Artist’s DNA

The older I get, the more I believe that what passes between artists is not simply influence or style, but something like genetic code, an artist’s DNA. It isn’t inherited by blood but by immersion, conversation, and example. The Bauhaus teachers handed it to Josef and Anni Albers, who passed it to their students at Black Mountain. From there, it traveled through Ken Noland’s disciplined color, through the dancers and painters at Bennington, through Woodstock’s rural classrooms, and finally into the hands of anyone who lived and worked inside those ideas, myself included.

That code insists that art and life are one field. I see its trace every time I look around my apartment, which I long ago turned into a painting I could live inside. The walls, furniture, plates, lamps, and rugs all belong to the same composition. It isn’t decoration; it’s continuity — the Bauhaus ideal translated into daily life. Living that way isn’t eccentric to me; it’s the natural conclusion of an education that made no distinction between making a meal, making a chair, or making a painting.

Continuum

When I look back now, I see how these schools shaped not only my thinking but my sense of what art can do. Each was an experiment in how to live, and in each I learned that the creative act is inseparable from the community that sustains it. The lesson endures: education, at its best, is itself a work of art.

Further Reading

The Bauhaus Group: Six Masters of Modernism by Nicholas Fox Weber

Leap Before You Look: Black Mountain College 1933–1957 (Yale University Art Gallery)

Bennington Modernism: Innovation in an Era of Anxiety by Jonathan D. Katz

A Brief History of Woodstock Country School (woodstockcountryschool.com)

Film Recommendation

Bauhaus: The Face of the 20th Century (BBC, 1994)

Black Mountain College: Experiment in Art (2002)