ARTISTS HELPING ARTISTS, Part 1:The Early Acts of Kindness

Artists Helping Artists, Part I: The Early Acts of Kindness

It is not a secret that I am obsessed with nineteenth-century French art, but so are most people with an avid interest in art. Besides the extraordinary work produced, the interpersonal relationships are also highly interesting, both the rivalries and the mutual aid. Monet could not have survived without Bazille; the Impressionists probably would not have been shown without Caillebotte. Rodin both helped and undermined Camille Claudel. And, of course, what would have happened to Van Gogh without Theo?

Frédèric Bazille, The Improvised Field Hospital (also known as Monet after His Accident at the Inn of Chailly)-Bazille nursed Monet after his accident, while he stayed in a studio he shared with Bazille.

Monet and Bazille — The Studio on the Edge

Before Impressionism even had a name, Claude Monet and Frédéric Bazille were living hand-to-mouth in Paris. Bazille, the son of a wealthy Montpellier family, quietly paid Monet’s rent, bought his canvases, and shared his studio. He even purchased Monet’s Women in the Garden for 2,500 francs, an enormous sum at the time, simply to help his friend survive. Their shared studio at 9 rue de la Condamine became a refuge for Renoir, Sisley, and others who drifted in, hungry and broke.

When Bazille was killed in the Franco-Prussian War at twenty-eight, Monet said he had lost “the best friend I ever had, the one who fed me.” His words are not metaphor. Bazille literally fed him.

Paul Gauguin, A drawing of Gauguin and Pissaro

Pissarro — The Generous Mentor

Camille Pissarro was the quiet backbone of the group. Older than most of his peers, he welcomed younger painters into his circle, often providing food, materials, and steady encouragement. Cézanne called him “a father to us all.” Gauguin, too, came to Pissarro’s table when he could no longer feed his family. Pissarro’s letters are filled with practical kindness: “Come,” he wrote, “you will eat at my table and we will talk of painting.”

His generosity wasn’t glamorous; it was daily sustenance, the difference between continuing to paint or not.

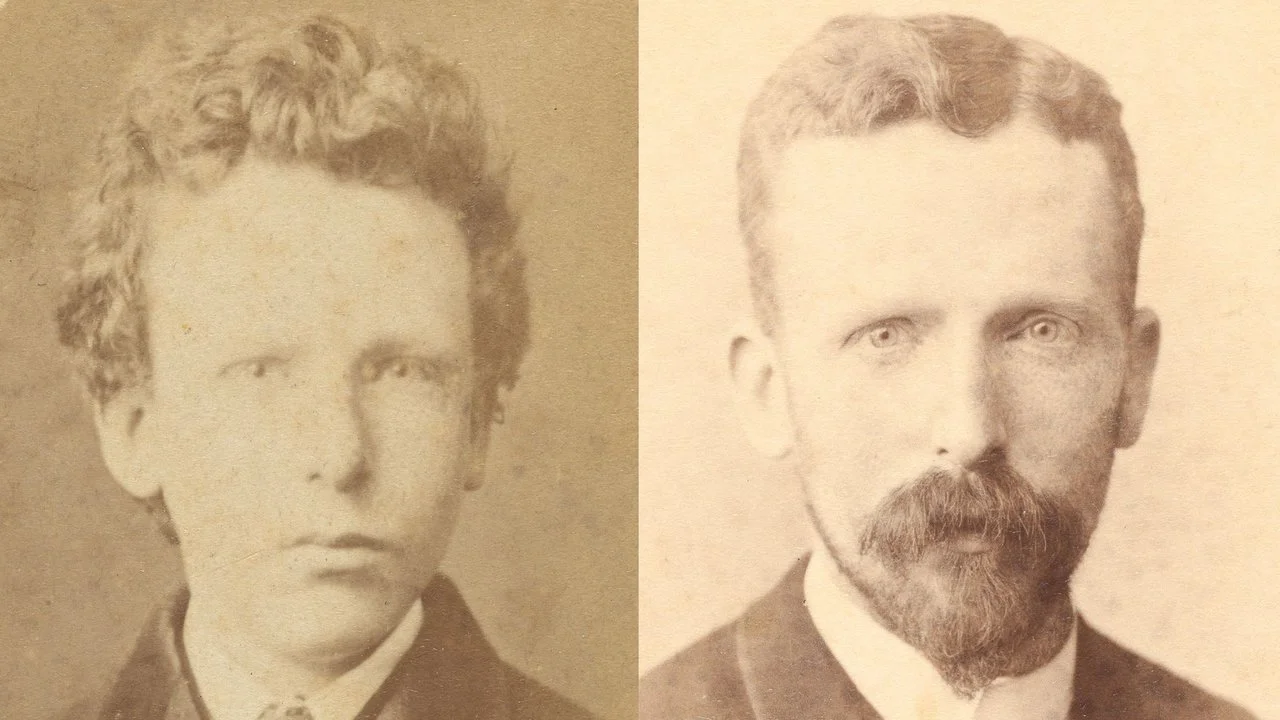

Vincent Van Gogh on the left and his brother Theo on the right.

Van Gogh and Theo — The Brotherhood of Survival

No story captures the material fragility of an artist’s life better than that of Vincent and Theo van Gogh. Theo sent his brother monthly allowances, paid his rent, bought his paints and canvases, and sustained him with letters full of belief. Virtually every painting we now revere, Sunflowers, Starry Night, The Bedroom, was financed by Theo’s love and labor.

Vincent’s legacy was Theo’s creation as much as his own brushwork; without that lifeline, there would be no Van Gogh as we know him.

Rodin and Claudel — Collaboration and Collision

Auguste Rodin’s relationship with Camille Claudel is more complicated. He recognized her brilliance early, took her into his studio, and introduced her to patrons and materials she could never have accessed alone. Yet he also absorbed her ideas, limited her independence, and used his power to define the narrative. Claudel’s later isolation was not just personal tragedy but a symptom of how easily generosity can curdle into possession.

Still, their shared years produced extraordinary work, each pushing the other toward new forms of expression.

Claude Monet, Le Déjeuner sur l’herbe (fragment), 1865–66. Oil on canvas, 130 × 181 cm. Musée d’Orsay, Paris. Public Domain.

The Hidden Economy of Friendship

In the nineteenth century, there were no grants, residencies, or fellowships, only the barter of trust, meals, and paint. Each act of generosity created a thread that held the fabric of modern art together. These artists were not only painting light; they were sustaining one another through darkness.

Further Reading

The Private Lives of the Impressionists by Sue Roe

Van Gogh: The Life by Steven Naifeh and Gregory White Smith

Film Recommendation