ARTISTS HELPING ARTISTS, Part 2: Built-In Generosity —The Communal Institutions

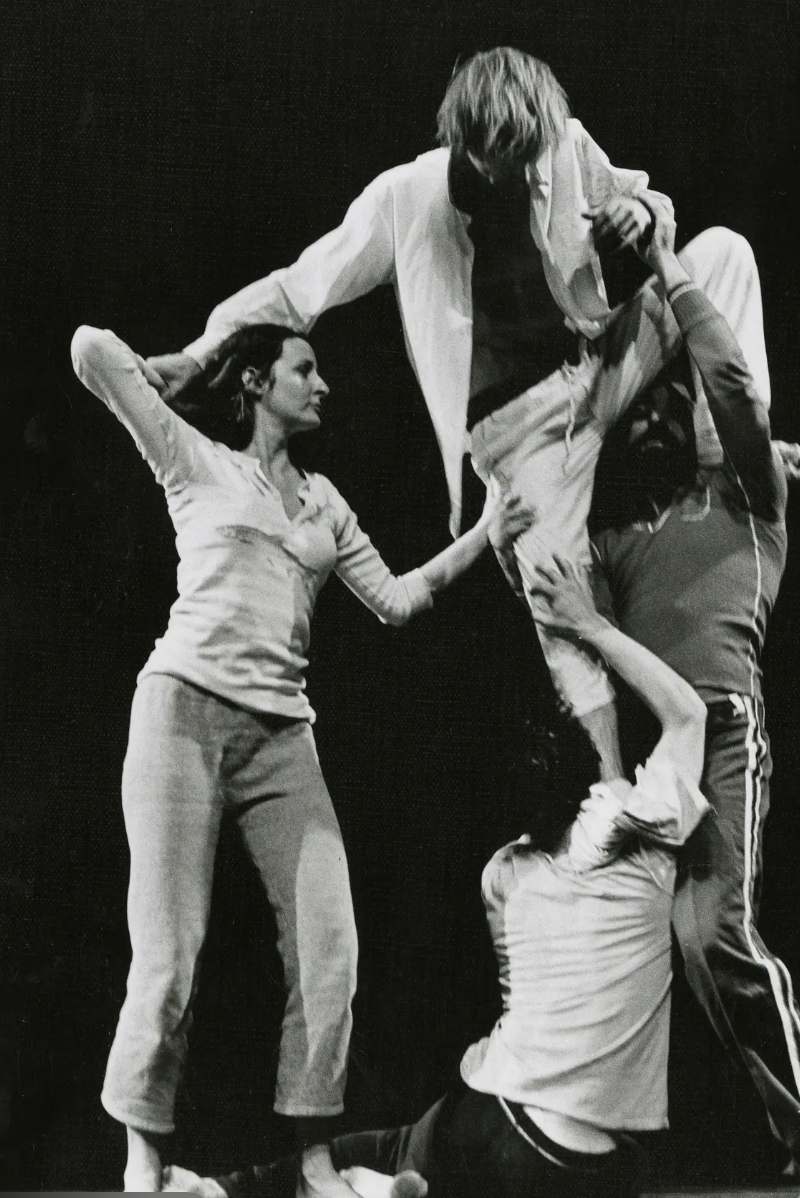

The Grand Union dance collective performing an improvisational piece. Four dancers, including Yvonne Rainer, Steve Paxton, Trisha Brown, and another member, support and balance one another in a sculptural formation on stage at Judson Dance Theater, New York, circa 1970s.

I was lucky enough to study contact improvisation with Steve Paxton when he taught dance at Bennington College, and to participate in a dance with Trisha Brown at the Whitney Museum Independent Study Program—the one summer it took place in New Mexico. So, it was no surprise to me to learn that Judson Dance Theater institutionalized generosity.

When dancing contact improvisation, you have to be completely attuned to the dancers around you. It’s a form where you literally feel your way through it—one person shifting weight, another offering balance, and both trusting that the floor, and each other, will be there. Trust is the foundation of this form of dance. People who understand this know that the welfare of those around you is intrinsically related to your own.

Lucinda Child’s Egg Deal in collaborative Concert #13, environment by Charles Ross, ph via MoMA

Judson Church — Trust as a Medium

That spirit of mutual reliance became the architecture of Judson Dance Theater in early 1960s Greenwich Village. When the church opened its parish hall to artists, it wasn’t a gesture of charity—it was a collaboration. There was no money, no hierarchy, and no guarantee that anyone would show up. Dancers, painters, and composers shared space, tape recorders, scaffolding, and time. If you had a lighting gel or a floor, you lent it; if you needed one, you borrowed it.

The exchange was material, but it was also moral: generosity became the rule of the room. Paxton’s and Brown’s work grew out of that physical democracy—an art form built on shared balance, not spotlight.

Genevieve Naylor Photo of Josef Albers Paper Folding at Black Mountain College

Black Mountain College — The Everyday Commune

Two decades earlier, Black Mountain College had already modeled that same ethos. Founded in 1933 as an experimental school, it made no separation between art and life. Students and teachers built the campus, farmed the land, cooked, cleaned, and taught one another. Josef and Anni Albers traded design instruction for labor and crops. If you couldn’t pay tuition, you worked it off.

Everyone was an artist, everyone was a caretaker. Rauschenberg later said it was where he learned that collaboration wasn’t a supplement to art—it was art.

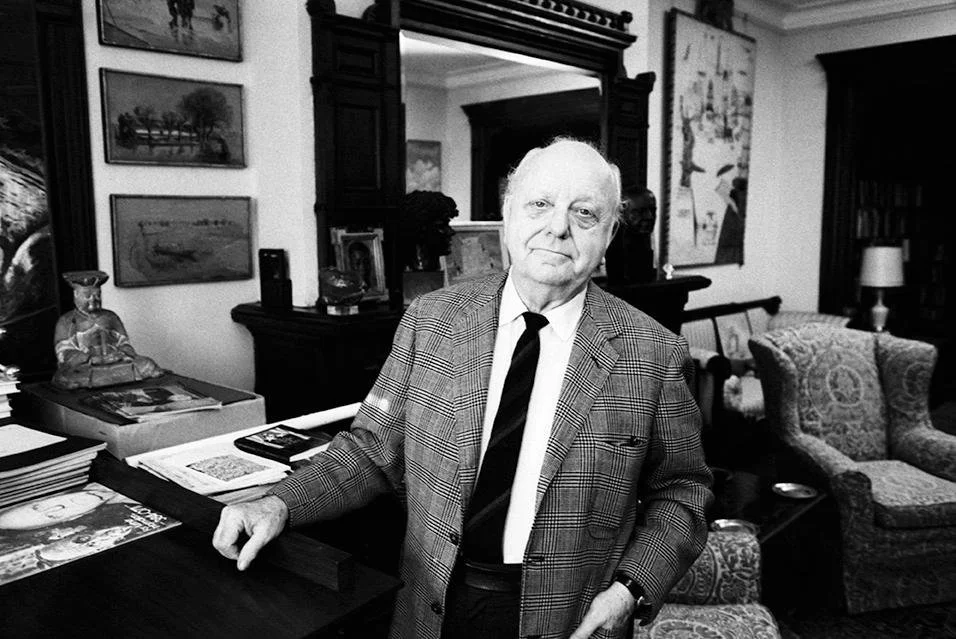

Virgil Thomson at the Hotel Chelsea, West 23rd Street, Manhattan, New York – a legendary residence for painters, writers and musicians from the 1960s through the 1990s

The Chelsea Hotel — Shelter and Exchange

By the 1950s, the Chelsea Hotel in New York extended that experiment into urban form. Painters, writers, and musicians traded art for rent or meals. Stanley Bard, the hotel’s manager, took paintings instead of cash and made sure his tenants could stay even when they were broke. The halls became a gallery of trust and debt—a living collection of promises kept.

Artists cared for each other there in literal ways: sharing heaters, typewriters, and, when necessary, rent checks. It was a messy, precarious generosity, but it kept creation alive.

When Community Is the Medium

From Judson to Black Mountain to the Chelsea, generosity was not an accessory to art—it was the medium itself. These were ecosystems where artists understood that creativity depends on connection, that the survival of one strengthens the survival of all.

When community is the medium, art flourishes.

Further Reading

Leap Before You Look: Black Mountain College 1933–1957 (Yale University Art Gallery)

Sally Banes, Democracy’s Body: Judson Dance Theater, 1962–1964

Film Recommendation

Merce Cunningham: A Lifetime of Dance (2000, PBS) — features the Judson lineage and how generosity and trust became choreography.

Optional pairing: The Chelsea on the Rocks (2008, dir. Abel Ferrara) — a rough-edged portrait of the hotel as living commune.