BETWEEN PALETTE AND PROPAGANDA: Emil Nolde’s Troubled Dance With Nazi Germany

Nolde’s story warns that persecution alone does not equal resistance: an artist can be both victim and believer, oppressed by aesthetic policy yet thrilled by the ideology behind it. For museums and viewers, the question is not whether to hang his blazing reds and violets, but how—with letters, party documents, and wall texts that refuse the old romance of the misunderstood genius.

Great art, like great history, demands the full palette—even the colours we’d rather leave in the dark.

Emil Nolde liked to think history had cast him as the misunderstood genius: too wild for the brown-shirt taste of the Third Reich, too German for the Paris-leaning modernists, forever persecuted for the fiery hues that blazed from his canvases. The truth, long folded into private letters, is knottier than that legend—and far more human.

A HOPEFUL COURTSHIP

When Adolf Hitler seized power in 1933, the fifty-something Nolde did not recoil in horror; he wrote letters of congratulations. He had spent a decade railing against “foreign”—he often meant “Jewish”—influences in German art, and the new regime seemed to promise exactly the cultural cleansing he craved. From his thatched studio on the windswept Danish border, he mailed sample portfolios to Joseph Goebbels, suggesting murals that would celebrate Nordic myth and peasant virtue. Visitors recall him pacing the room and announcing, “The Führer will understand my art!”

Works such as The Last Supper (1909), a tangle of lemon-yellow halos and greenish Christ flesh, and Crucifixion (1912), all stabbed carmine, seemed to Nolde the perfect spiritual language for a reborn German nation. His earlier iconoclasm would, he believed, be re-read as prophecy.

THE BREAK-UP

Then came 1937. Inside Munich’s Haus der Kunst, Hitler’s curators hung thirty-three Noldes under the sneering banner Entartete Kunst—Degenerate Art—beside jeering labels about “perverted colour.” Worse still, more than a thousand other works were yanked from German museums and storage rooms, the single largest purge of any artist. Nolde had not anticipated how sharply Nazi taste would pivot toward muscular neo-classicists like Arno Breker.

Stung, he doubled down on loyalty. Letters from that summer show him assuring Goebbels that his “true German spirit” had been misunderstood by lesser bureaucrats. But the wheel kept turning. In 1941 a Malverbot—a professional ban—arrived: no exhibitions, no sales, no oil-paint coupons. Officially, Emil Nolde the painter ceased to exist.

THE LEGEND OF THE LOCKED DRAWER

This is where Nolde’s post-war myth takes root. Unable to stretch canvases, he turned to small water-colours, the so-called “Unpainted Pictures.” These fit in a drawer, easy to hide if officials visited. After the war he told interviewers he had painted them furtively in defiance of tyranny—proof, he suggested, that his spirit had resisted the very powers that silenced him.

Yet archive stamps tell a subtler story. Many sheets date from 1938 or 1939, before the ban. Others carry 1943 notations in fresh oil. The painter may have lost his public platform, but alone in Seebüll he was never truly gagged.

REHABILITATION AND RECKONING

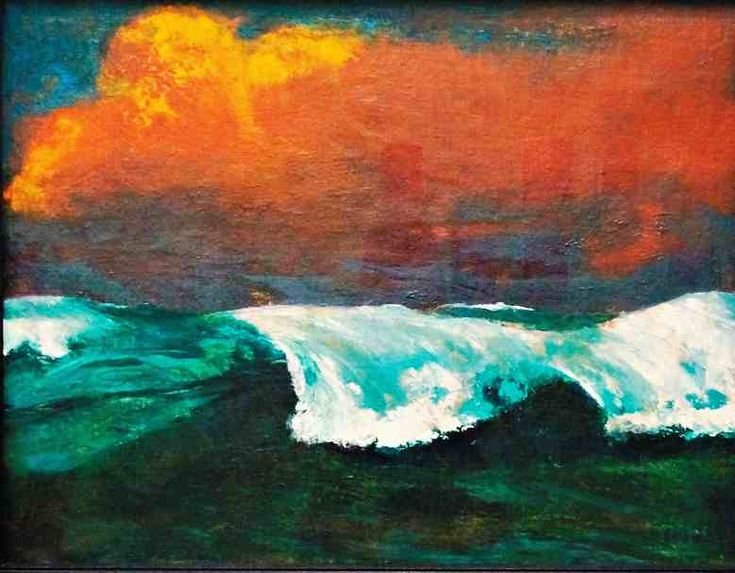

Post-1945 West Germany was starved for heroic modernists untainted by Nazi fervour. Nolde’s confiscations looked like a badge of martyrdom; his antisemitic writings stayed locked in family files. Exhibitions of glowing flower fields such as Blumengarten and surf-roaring seascapes like Brecher presented a newly apolitical genius, nature-mystic rather than nationalist zealot.

The legend held for decades. Chancellor Angela Merkel even hung Brecher behind her desk. Then, in 2019, Berlin’s Neue Nationalgalerie pried open the Seebüll archive for “Emil Nolde – A German Legend.” Visitors read, in Nolde’s own handwriting, praise for Hitler dated 1942 alongside private jabs at “Semitic corruptors.” Merkel quietly removed the seascape from her office wall.

SEEING THE PAINTINGS NOW

Stand in front of Pillars of Fire (1929)—all cobalt blues stabbed with orange flame—and you feel raw spiritual electricity. Know that the painter later begged a totalitarian state to recognise that power, and the jolt becomes complicated. Likewise, the jewel-like Unpainted Pictures shimmer with secrecy, but secret loyalty as much as secret rebellion.

None of this dims the colours. It does, however, stain them with history’s after-image, reminding us that aesthetic brilliance and political belief can occupy the same brushstroke.

Nolde’s life warns that an artist can be both sanctioned and complicit, censured and enthralled. The task for museums—and for us—is not to decide whether his violets and vermilions deserve wall space. It is to hang the letters beside the paintings, to let the full, difficult spectrum glare in the light, so we see not only what genius can create, but what it can excuse.

Written with help of AI