FOOD DIPLOMACY: HOW MEALS HAVE SHAPED WORLD POLITICS

History is full of treaties written in ink—but many were sealed in sauce. "Food diplomacy" may sound quaint, but it has altered borders, changed empires, soothed enemies, and occasionally humiliated them. The table has always been a stage, and the meal a weapon or an olive branch. From Carême’s diplomatic cuisine to modern photo‑op hamburgers, the evolution of political dining tells us exactly how power works—and how it tastes.

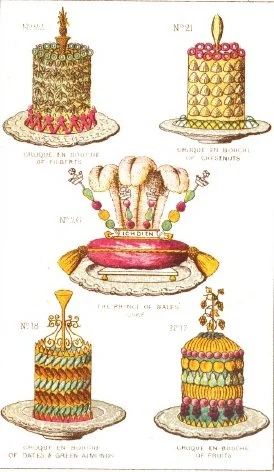

A few of Carêmes dishes

CARÊME AND THE INVENTION OF DIPLOMATIC CUISINE

Marie‑Antoine Carême, the world’s first celebrity chef, was hired by Talleyrand not merely to cook but to negotiate. Talleyrand believed the Congress of Vienna could be influenced as much by a well‑timed soufflé as by a speech. Carême’s food was architecture: towering pièces montées, geometric pâtés, sauces so refined diplomats felt morally obligated to behave.

Carême understood three rules of food diplomacy:

Feed them better than they feed you.

Never let a man make war on someone whose pastry he admires.

Beauty softens positions.

He helped Talleyrand charm rivals into allies—or at least into less troublesome enemies. In a world without public relations, Carême was the secret PR department of France.

Portrait of Antonin_Carême.

THE DINNER THAT MARKED INDIA’S INDEPENDENCE

(AND A WARNING SERVED ON A SILVER TRAY)

On the eve of Indian independence in 1947, Lord Louis Mountbatten—Britain’s last Viceroy—hosted an elaborate dinner for Indian dignitaries, politicians, and soon‑to‑be national leaders. The menu was deliberately extravagant, even by Raj standards. According to several accounts, Mountbatten insisted the dinner be lavish enough to remind India of what it was losing as the British departed.

It was a final performance of the imperial theater: crystal, silver, imported wines, European courses. A carefully plated illusion of stability and elegance at the very moment the empire was collapsing.

The irony: the dinner did not inspire nostalgia. It became a symbol of the colonial disconnect—a feast held on the brink of upheaval, as famine and sectarian violence gripped the region.

Food diplomacy, when misjudged, reveals more than it masks.

Viceroy's House, now Rashtrapati Bhavan (Hindi for "President's House"), Raisina Hill, New Delhi, India;

THE QUEEN’S DINNERS: THE SOFT POWER GOLD STANDARD

Queen Elizabeth II’s state dinners were less about indulgence and more about ceremony as diplomacy. Everything—from the placement of a water glass to the angle of a folded napkin—reinforced stability, civility, and the continuity of the British state.

The state banquet held for China's Xi Jinping and his wife, Madame Peng Liyuan in 2005 WPA Pool/Getty Images

President Barack Obama and Queen Elizabeth II during a State Banquet in Buckingham Palace

A few dinners of political significance:

1957, Eisenhower at Buckingham Palace: A post‑Suez crisis charm offensive designed to repair the strained US‑UK relationship. The Queen deployed subtlety—venison, trout, and wines chosen to flatter American tastes.

1976 Bicentennial Visit: The Queen, knowing the historical irony, toasted the United States’ "friendship and partnership"—over a menu blending British formality with American ingredients. Soft power is often served in consommé.

Obama, 2011: The menu intentionally avoided extravagance: warm-weather English vegetables, lamb, and a restrained pudding. The message: modern Britain, updated traditions.

The Queen understood what Carême knew: diplomacy tastes better when formality is comforting rather than intimidating.

THE KENNEDY WHITE HOUSE: WHEN STYLE BECAME STRATEGY

The Kennedy’s Entertaining

If Talleyrand invented diplomatic dining and the Queen perfected it, Jacqueline Kennedy glamorized it.

Her state dinners were performances of American modernity: French chefs, American wines, art on loan from museums, menus typed with an aesthetic eye.

Dinners of note:

1961, Tafari Makonnen (later Haile Selassie): A dazzling blend of French cuisine and African musical tributes. The message: America sees you.

1962, Nobel Prize Winners Dinner: Not political, but symbolic—Kennedy reminding the world that American intellect was its own form of soft power.

1962, President de Gaulle: Jackie used French cuisine as a diplomatic mirror. De Gaulle bristled at American attempts at elegance, but the dinner softened him.

Where Eisenhower’s dinners were hearty and Republican, the Kennedys curated aspiration.

WHEN FOOD BECOMES A SWORD

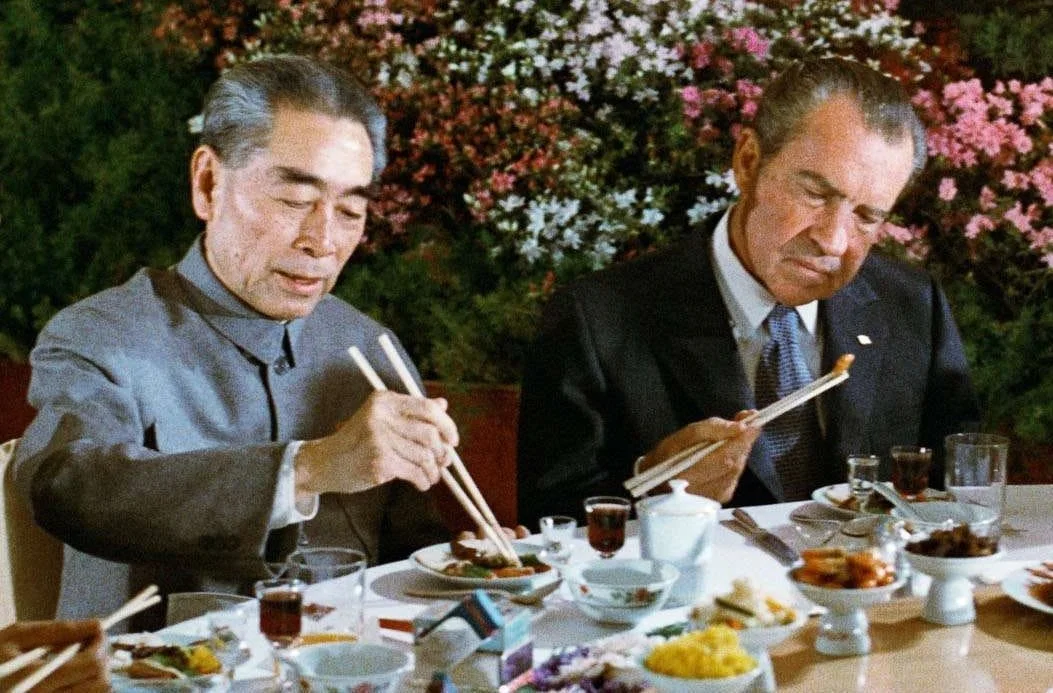

Richard Nixon eating with Zhou Enlai and Chang Chun-chiao in Shanghai. Photograph: Bettmann/Bettmann Archive

Diplomatic meals can wound as easily as they charm.

Nixon in China, 1972: Mao and Zhou Enlai used banquets to test Nixon’s reactions—serving dishes symbolizing endurance, unity, and occasionally coded threats.

Putin’s meals with world leaders: often heavy with meaning—honey from Crimea, fish from disputed waters.

Middle Eastern summits often hinge on whether kosher, halal, or neutral menus are chosen. One wrong dish can undo weeks of negotiation.

Food is never just food.

THE McDONALD’S WHITE HOUSE ERA: THE END OF DIPLOMATIC THEATER

And whatever this is.

In recent years, certain high‑profile White House "dinners" featuring fast food towers—McDonald’s, Burger King, Wendy’s—were framed as populist gestures. But diplomatically, they functioned as performative rejection of tradition.

Instead of Carême-level choreography, the message was:

"We no longer value the ceremony. We no longer play the game."

This may please a domestic audience, but on the world stage it signals disinterest in the rituals that keep alliances lubricated.

Food diplomacy has always been a language. This shift is, essentially, a refusal to speak it.

THE MEAL AS MESSAGE

FILM & TELEVISION: FOOD DIPLOMACY ON SCREEN

Several films and television series portray food as a diplomatic tool—or as the emotional battleground of political relationships.

• The King’s Speech (2010) – While not centered on a meal, the film includes scenes of royal ceremonies and diplomatic hosting that highlight soft power, ritual, and tradition.

• The Crown (Netflix) – Multiple episodes portray state dinners, especially those involving Eisenhower, Kennedy, and Obama. The show captures exactly how the Queen used hospitality as policy.

• Jackie (2016) – Features the reconstruction of Kennedy White House dinners and Jackie’s use of French cuisine as soft power.

• Nixon in China (opera, filmed versions) – The banquet scene is iconic: Mao’s court uses food to test Nixon’s reactions and convey coded messages.

• Babette’s Feast (1987) – Not diplomatic per se, but Carême-inspired, and a perfect study in how food transforms relationships and power dynamics.

• The Reluctant Fundamentalist (2012) – Includes scenes in which American hospitality and power are contrasted during formal meals.

• The Last Viceroy / Viceroy’s House (2017) – Dramatizes Mountbatten’s final months in India, including ceremonial dinners meant to convey imperial dignity at the end of empire.

• The American President (1995) – A lighter depiction, but the White House dinner scenes capture the calculated use of food and hosting.

• House of Cards (Netflix) – Multiple episodes show meals as weapons: who sits where, what is served, and who refuses to eat.

Whether in the hands of Carême, the British monarchy, or the Kennedy White House, political meals tell stories:

We honor you.

We understand your culture.

We are equals.

Or, occasionally: We don’t care.

Food diplomacy isn’t about the menu—it’s about the mood, the signaling, the choreography. The most successful political meals whisper rather than shout.

What Carême understood remains true today: nations negotiate with their minds, but they decide with their appetites.