THE SUN KING AT SUPPER: HOW LOUIS XIV TURNED DINING INTO POWER

(With film and TV scenes that bring it vividly to life)

If you have ever walked into a fine restaurant and felt a little smaller, a little more aware of your posture, or a bit uncertain about your knife, you may be experiencing the long shadow of Louis XIV. The Sun King did not invent haute cuisine to delight the palate. He created a world in which eating was a political act. The food was beautiful, but the real purpose was control.

When Louis took power, the French nobility was powerful and restless. They lived on their own estates, built their own alliances, and occasionally challenged the throne. Louis saw immediately that the state could not function while everyone with a title operated like a minor king. His solution sounds gracious on the surface. He invited them all to live with him at Versailles. Once they arrived, they were not meant to return home. They were there to orbit the king.

Versailles became a golden cage. What kept people inside was not force. It was ritual. The days were organized into ceremonies that required constant participation. People competed obsessively for the smallest privileges, because each one reflected royal favor. Even eating became a mechanism of control. Louis ate in public at the evening meal known as le grand couvert. Nobles gathered in arranged rows and watched him dine. Simply being permitted to hand him a napkin was a high honor. Presenting a dish was practically a career achievement. These tiny gestures kept the nobility in a state of constant emotional readiness.

It is one thing to attend a dinner. It is another thing entirely to build your future around the possibility of handing the king a spoon. That kind of system rewires a person.

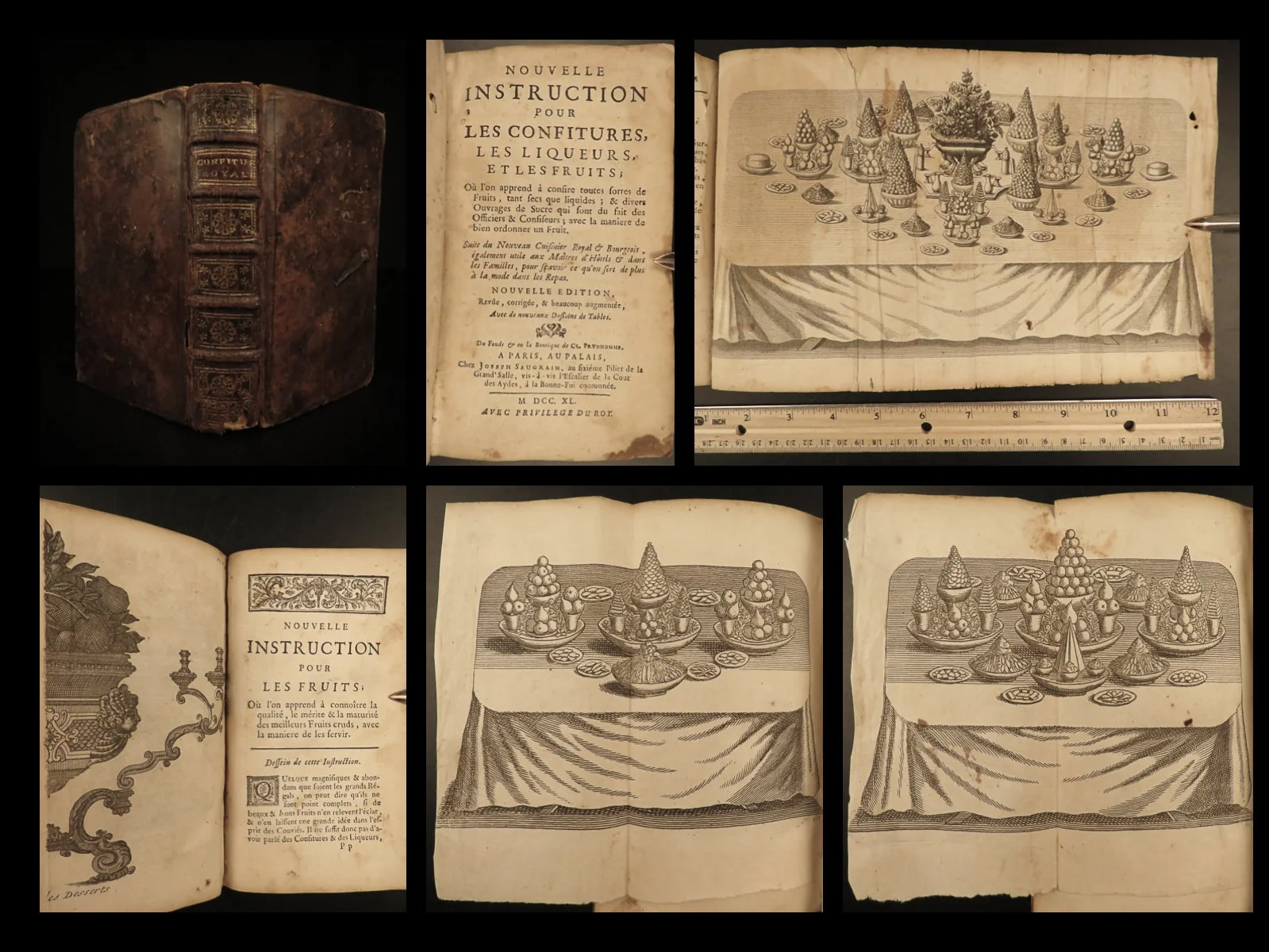

The kitchens at Versailles responded to this culture by elevating their craft. Before Louis, French cooking still carried traces of medieval habits. Spices were used to mask inferior ingredients. Dishes were combined without a clear sense of structure. As the court grew more theatrical, the food followed. Cooks developed organized courses, refined sauces, and presentations that looked like stage sets. They made sugar sculptures, architectural pastries, molded gelées, and fantastical feasts. There were pies from which live birds emerged when the crust was cut. There were roasts constructed from multiple birds nested inside one another. Everything was created to dazzle the eye and confirm the king’s power. If the rest of the country was hungry, that was not reflected in the king’s dining room.

Chefs like La Varenne and Massialot began writing down techniques and menus that shaped the earliest foundations of French cuisine. They were not celebrities. They were craftsmen working inside a system that demanded spectacle. Their work laid the groundwork for the culinary codification that would come a century later under masters like Carême and Escoffier.

The real brilliance of Louis’s system was not the food. It was the psychology. The nobles were so preoccupied with the rituals of dining that they had no time to build opposition. People who once commanded armies now spent their mornings rehearsing how to bow at exactly the right angle. Dining was not leisure. It was surveillance. It was a reminder of one’s place. It was a daily enactment of rank.

This is one reason haute cuisine can still carry a faintly intimidating charge. Fine dining uses silence, precision, and choreography. These elements began as instruments of control. Even today, when a single scallop arrives on a plate like a sacred object, some ancient instinct recognizes that this style of eating was born in a world that associated food with hierarchy.

On Screen: Versailles and the Spectacle of Power

If you want to see the theatricality of Louis XIV’s dining rituals brought to life, the series Versailles (Canal+ and Netflix) offers a vivid portrait. The scenes of le grand couvert capture the strange mixture of beauty and tension that defined court life. Everyone smiles, everyone sparkles, and yet you can feel the pressure under the silk. A dining room becomes a political arena.

Other films echo this world even if they focus on different monarchs.

Marie Antoinette (Sofia Coppola) shows the lingering influence of Louis’s rituals, especially in the formal breakfasts and elaborate desserts. In that film the food functions as both pleasure and suffocation.

The Favourite uses meals as demonstrations of favoritism, rivalry, and humiliation. While set in England, the emotional mechanics are deeply similar to Versailles.

Even Dangerous Liaisons shows how food serves as a stage for seduction, manipulation, and status. The dining scenes function almost like duels fought with silverware.

If you want an image of how intimidating courtly meals could be, these are perfect places to look.

Versailles is a lavish historical drama centered on the early reign of Louis XIV, at the moment when he decides to move the French court from Paris to Versailles and transform a modest hunting lodge into the most theatrical seat of power in Europe.

Set primarily in the 1660s–1670s, the series treats Versailles not simply as architecture but as a political instrument. Louis, young and newly sovereign, understands that absolute power cannot rely on force alone. It must be staged, ritualized, and endlessly observed. The court becomes a carefully engineered ecosystem where proximity to the king determines survival, and every gesture—dressing, dining, sleeping—is freighted with consequence.

The show is unapologetically sensual and brutal. Sex, violence, illness, and excess are not ornamental; they are presented as part of governance. Bodies are political. Desire is leverage. Food, banquets, and public rituals function as mechanisms of control, echoing the historical reality of the lever, the coucher, and the grand couvert, in which the king’s daily life becomes a form of surveillance theater.

Visually, Versailles leans into Baroque excess rather than documentary restraint. Candlelight, silk, blood, gold, and shadow dominate the frame. The tone is deliberately modern in pacing and explicitness, closer to prestige television than heritage drama, which makes its argument about power feel contemporary rather than antiquarian.

Historically, the series takes liberties. Timelines compress, characters are heightened, and psychology sometimes outruns the archive. But its central thesis is sound: Versailles was not built for comfort or beauty alone. It was built to trap the nobility inside ritual, to turn aristocrats into performers, and to ensure that nothing—least of all the king’s body—was ever private.

In short, Versailles is less about Louis XIV as a distant monarch and more about how power is manufactured through spectacle, making it particularly resonant for conversations about food, etiquette, and visibility as instruments of rule.

The Echo That Never Quite Fades

Louis XIV turned eating into a performance that revealed power. The rituals outlived him. They shaped the structure of restaurants, the expectations of service, and the emotional undercurrent of luxury. They even shaped the way films portray aristocratic dining. What began as a political strategy now lives quietly inside the gestures of waiters, the arrangement of courses, and the feeling that some meals are meant to be admired rather than consumed.

The next time you sit down in a restaurant where the plates arrive like little ceremonies, you might sense a faint whisper from that long dining hall at Versailles. You may feel it in your posture. You may feel it in the silence. You may even feel it in the first bite.

Louis XIV understood that the easiest way to rule people was not through force. It was through ritual. A meal, served with enough ceremony, can hold a nation in place.

And sometimes it still does.