THE HANGOVER

Every story about artists and bars eventually needs a morning-after chapter. This is it.

It’s tempting to treat drinking as part of the atmosphere, like bad lighting or loud music. Something incidental. Something that belongs to the room rather than the body. And for a while, it does. Conversations loosen. Arguments sharpen. People stay later than they should. Work gets talked about intensely, if not always made.

But alcohol is not neutral. It never was.

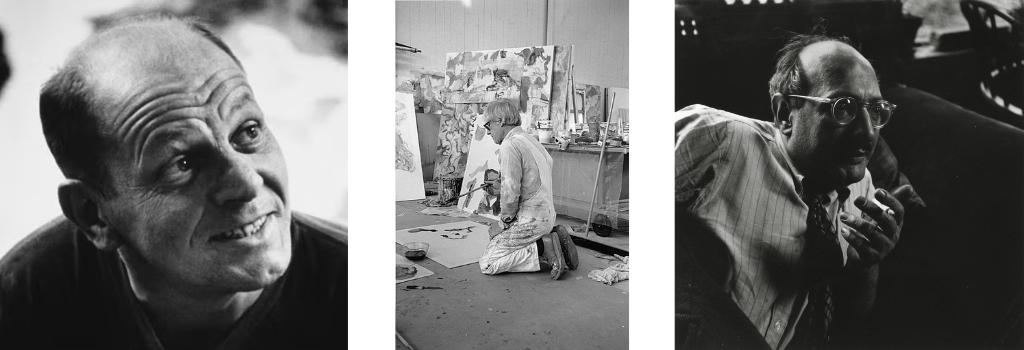

Pollock, deKooning, Rothko

The mythology is familiar enough that it barely needs repeating. Jackson Pollock looms largest, partly because his work was revolutionary, partly because his end was cinematic, and partly because the culture prefers a clean, dramatic conclusion. Willem de Kooning complicates the story. He drank for decades, stopped, and kept working. That fact alone makes people uncomfortable. It disrupts the idea that the bottle was doing the heavy lifting.

Mark Rothko’s isolation is harder to romanticize. Drinking sits there quietly, not as bravado, not as fuel, but as something narrowing his world. Franz Kline is often remembered for scale and force, less often for how little time he had. Early death gets smoothed over when the paintings look confident enough.

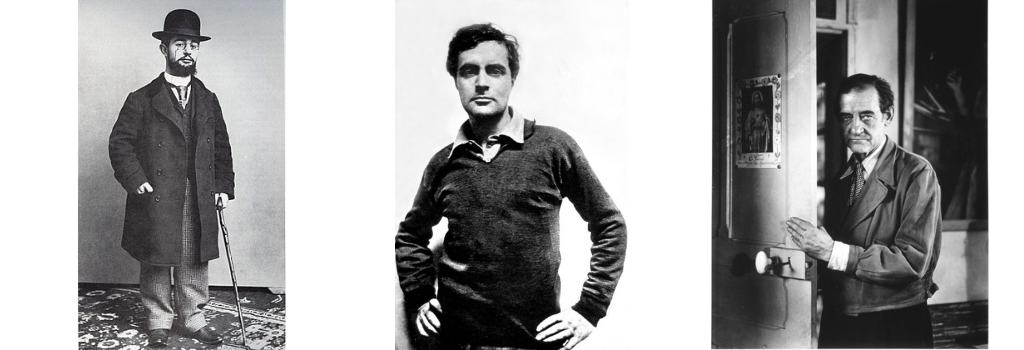

Paris offers no refuge from the pattern. Toulouse-Lautrec helped invent the image of the artist dissolved into the night, absinthe glass in hand. The image stuck. The cost did too. Maurice Utrillo makes the café story much less charming. His drinking wasn’t witty or theatrical. It was disabling, managed by others, survived rather than conquered. Modigliani is still romanticized, which doesn’t help. Talent has a way of encouraging people to look away from the obvious.

None of this is news. That’s the point.

Toulouse-Lautrec, Modigliani, Utrillo

The danger isn’t that people don’t know. It’s that the costs get absorbed into the legend and disappear. Drinking becomes part of the décor, like a bar stool or a chipped glass, while the damage gets edited out of the story we like to tell.

This isn’t an argument against bars, or conversation, or the pleasure of staying out late with people who care deeply about the same things you do. It’s just a reminder that the work didn’t come from the alcohol. It happened around it. Sometimes despite it.

By morning, what’s left is simpler. Some people kept working. Some needed help. Some didn’t make it. The myth survived all of them.

That’s the hangover.