DORA CARRINGTON AND LYTTON STRACHEY: Love Without a Center

If Vanessa Bell built a life around coherence, Dora Carrington and Lytton Strachey lived inside a more unstable geometry. Their relationships were not anchored by truth-telling in the Bell sense, nor by the steady negotiation that held Charleston together. What animated Carrington and Strachey was something else entirely: intensity without reciprocity, devotion without symmetry, love without a shared object.

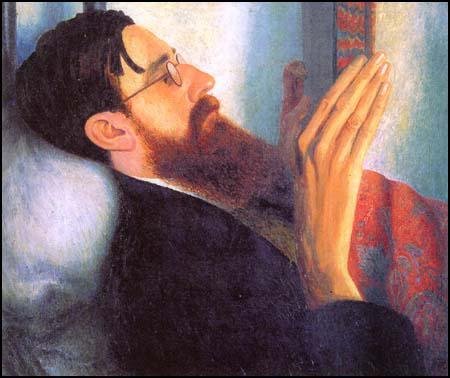

Dora Carrington, Lytton Strachey 1916 © National Portrait Gallery, London

Carrington fell in love with Lytton Strachey almost immediately. He did not return her desire in any conventional sense. He was gay, emotionally exacting, and deeply attached to her, but not as a lover. He wanted her closeness, her loyalty, her presence, without the bodily or romantic exchange that would have clarified the bond. Carrington accepted these terms, not because they made sense, but because the pull was absolute.

This is where her story diverges sharply from Vanessa Bell’s. Bell revised institutions; Carrington suspended them. Bell made structures bend; Carrington erased them altogether.

Dora Carrrington, Ralph Partridge, and Lytton Strachey, Wikimedia Commons

When Ralph Partridge entered their lives, the arrangement became more legible and more impossible. Carrington married Ralph, not out of love for him, but to keep Strachey close. Ralph loved Strachey; Strachey loved being loved; Carrington loved Strachey and tried to live inside the triangle without naming its fractures. They moved together to Ham Spray House, a domestic arrangement built on displacement rather than balance.

Boyfriends and lovers passed through the periphery. Carrington had affairs with men, sometimes passionately, sometimes destructively. Strachey had relationships with men who were often emotionally distant or impractical. These attachments did not resolve the central tension; they intensified it. No one occupied the center because the center was already taken by a relationship that could not be consummated and would not release its hold.

The theme here is not honesty, exactly. It is fixation.

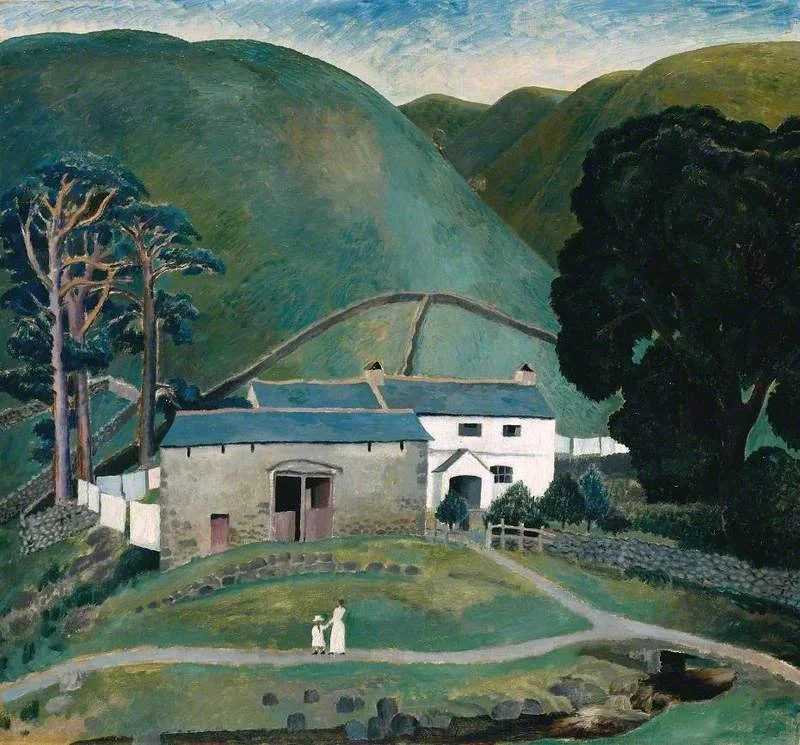

Carrington was a formidable painter, yet she consistently subordinated her work to the emotional weather of Strachey’s approval. Her letters, her moods, and her productivity rose and fell with his attention. Where Vanessa Bell allowed form to emerge from sustained looking, Carrington’s seeing was repeatedly interrupted by longing. Her talent was real, but it was never allowed to stabilize into authority.

Dora Carrington, Farm at Watendlath, 1921.

Strachey, for his part, was not cruel so much as absolute. He required devotion and assumed it as his due. He did not lie about who he was, but he did not consider the gravity he exerted on those who orbited him. Carrington mistook proximity for purpose. Ralph mistook endurance for love. Everyone mistook intensity for meaning.

This is why their story belongs in Love: It’s Complicated, but not as a celebration of lived truth. Their lives were not experiments in freedom. They were demonstrations of how desire can reorganize reality without ever making it habitable.

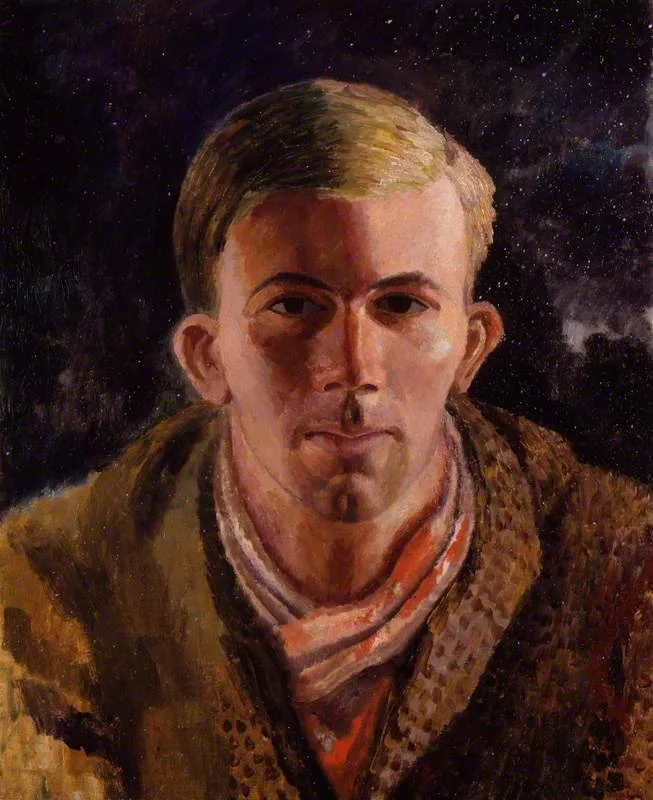

Girl in a Blue Jersey (Dora Carrington), Mark Gertler, Oil and Tempera on Canvas, 1912 (Huntington Art Gallery)

When Strachey died suddenly in 1932, the structure collapsed. Carrington could not reconstitute herself outside the field of his attention. Two months later, she took her own life. The tragedy is not only the loss, but also the recognition that she had never been allowed to imagine a life in which her work, rather than her devotion, was central.

Carrington and Strachey show us something Vanessa Bell does not: that complexity alone is not virtue. Love can be complicated and still be corrosive. Freedom without reciprocity is not freedom at all. And brilliance, when unmoored from self-regard, can burn inward rather than illuminate.

Their story lingers because it resists redemption. There is no manifesto to extract, no livable model to admire. What remains is a cautionary figure for modern intimacy: a reminder that attention is not neutral, that asymmetry accumulates, and that love, without a center that can hold more than one life, eventually collapses under its own weight.

Later accounts sometimes suggest a second marriage to Bernard Penrose, but this was only a briefly imagined future; Carrington died two months after Strachey, before any new life could take shape.

Sidebar: A Hum of Attachments

Dora Carrington, Brenan

Around Carrington and Strachey, relationships rarely aligned. Carrington loved Lytton Strachey; Strachey loved men, including Ralph Partridge, who married Carrington to remain close. Carrington had affairs with Gerald Brenan and others; Strachey drifted through attachments that rarely lasted. Henrietta Bingham passed briefly between them. Love moved sideways, never landing. No one deceived exactly, but no one was centered either.