WHEN ARTISTS CAN’T SEE CLEARLY

Claude Monet, The Japanese Footbridge (1899, France) - Painted before cataracts. Claude Monet (1840–1926, France), The Japanese Footbridge, 1920–1922. Oil on canvas, 35 1/4" x 45 3/4" (89.5 x 116.3 cm). © The Museum of Modern Art, New York. (MOMA-P2623) - Painted after cataracts.

I’ve been thinking about eyesight lately, for obvious reasons. Cataract surgery is on my horizon, and as a painter, the prospect of altered vision feels both frightening and strangely fascinating. Artists have always made work with the bodies and eyes they have—sometimes diminished, sometimes distorted—and the art often bears witness to those changes.

Claude Monet is the classic example. His cataracts muddied his late canvases, drowning them in reds and browns, washing out the water lilies and garden that had once been luminous. After surgery, he suddenly saw blues so intensely that he complained about them. His palette, and the way we see his world through him, shifted with the state of his eyes.

Claude Monet, Irises, 1923–1926. Oil on canvas, 78 3/4" x 79 1/4" (200 x 201.3 cm). © Art Institute of Chicago. (AIC-7266)

Edgar Degas lost central vision to macular degeneration. His earlier works were precise, every line etched, but later the edges blur, forms dissolve, colors vibrate. The dancers remain—but they are softer, more about the rhythm of gesture than anatomical detail. Georgia O’Keeffe suffered the same disease decades later. She never stopped creating. When her flowers became impossible, she moved into clay, still making beauty tactile, still working with her hands when her eyes betrayed her.

El Greco’s case is murkier. His elongated saints and stretched Christs have long been attributed to astigmatism, as if he couldn’t see straight. Maybe. Or maybe he simply saw differently—his distortion a deliberate vision, not an affliction. Either way, the speculation reminds us how inseparable sight and style can be.

El Greco (Domenikos Theotokopoulos), “Portrait of an Old Man,” ca. 1595–1600

And then there is Chuck Close, who couldn’t recognize faces in life but painted them relentlessly. His face blindness meant he broke down every portrait into tiny units—grids, cells, marks—until the whole emerged from parts. Later, after paralysis confined him to a wheelchair, he adapted again, brush strapped to his hand, determination intact. His work reminds me that constraints can become structure, that difficulty itself can generate form.

Chuck Close, “Self-Portrait”

Francisco de Goya is another example. In old age, nearly deaf and nearly blind, he produced the Black Paintings—hallucinatory, terrifying visions plastered directly on the walls of his house. Were they the product of failing vision, or of a failing world? Both, perhaps. His blindness and deafness drove him inward, and what he saw there was not darkness, but ferocity.

Goya, detail.

Vincent van Gogh’s case is more speculative. Some argue that his swirling halos and blazing yellows reflected xanthopsia—yellow vision—possibly brought on by medications or lead poisoning. Whether or not the science is right, it’s clear his perception was altered, and he painted the world as if it were alive, vibrating, trembling at the edges of sight.

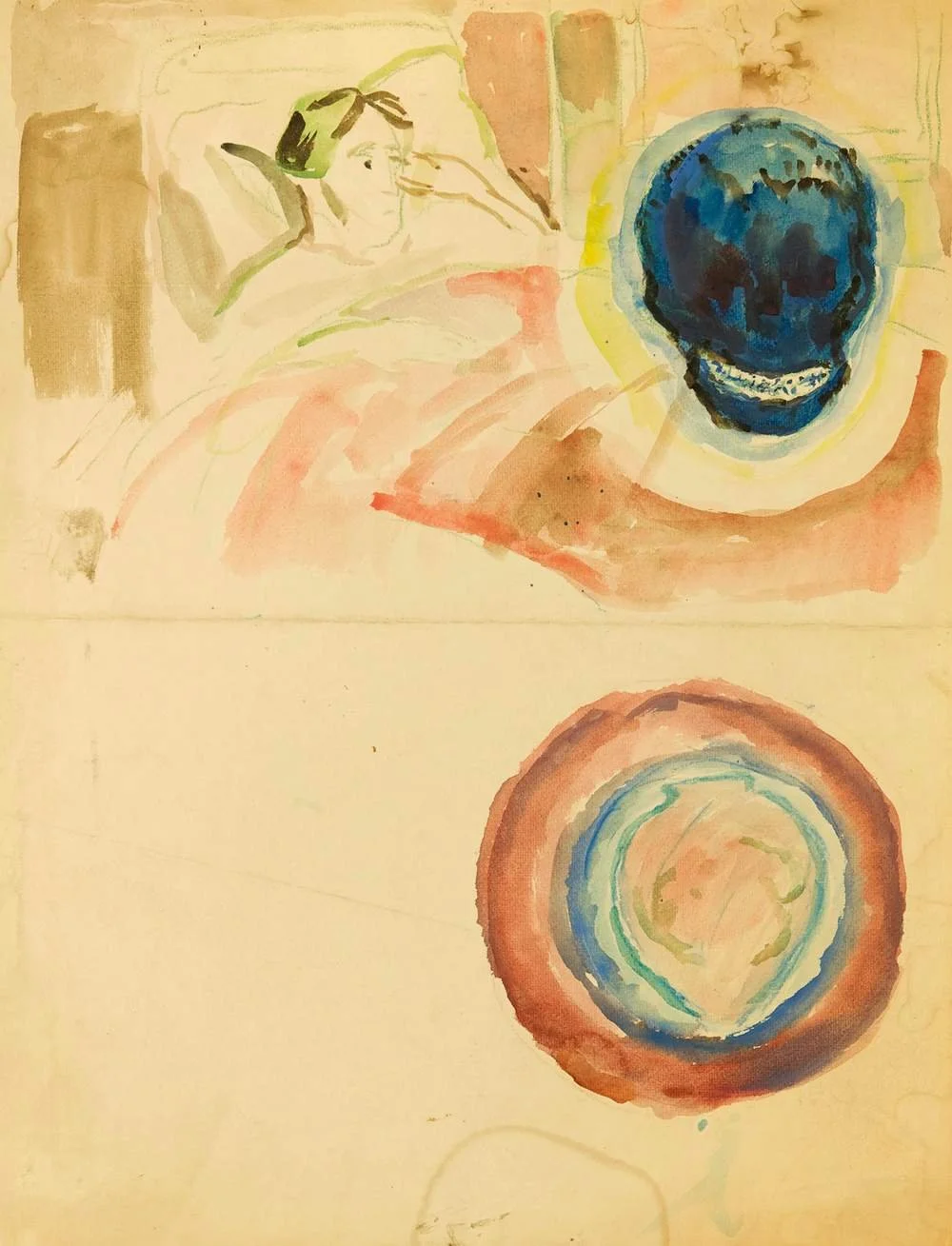

Edvard Munch, by contrast, documented his vision loss explicitly. After a hemorrhage in his eye, he sketched what he saw: blind spots, flashing lights, distortions across the page. He turned his impairment into subject matter, charting the changes in his own retina with the same honesty he once brought to The Scream.

I don’t yet know how my own vision will shift after surgery. But I take comfort, and even inspiration, in knowing that the history of art is filled with eyes that faltered, adapted, and kept looking. Sometimes that change in vision opened the way to something rawer, stranger, or more profound. In the end, it may not be perfect sight that matters most, but the persistence of looking.

When I have found articles with more details about the artist’s eye condition I have attached it to the photo of their work.