WHEN THE BRAIN SEES

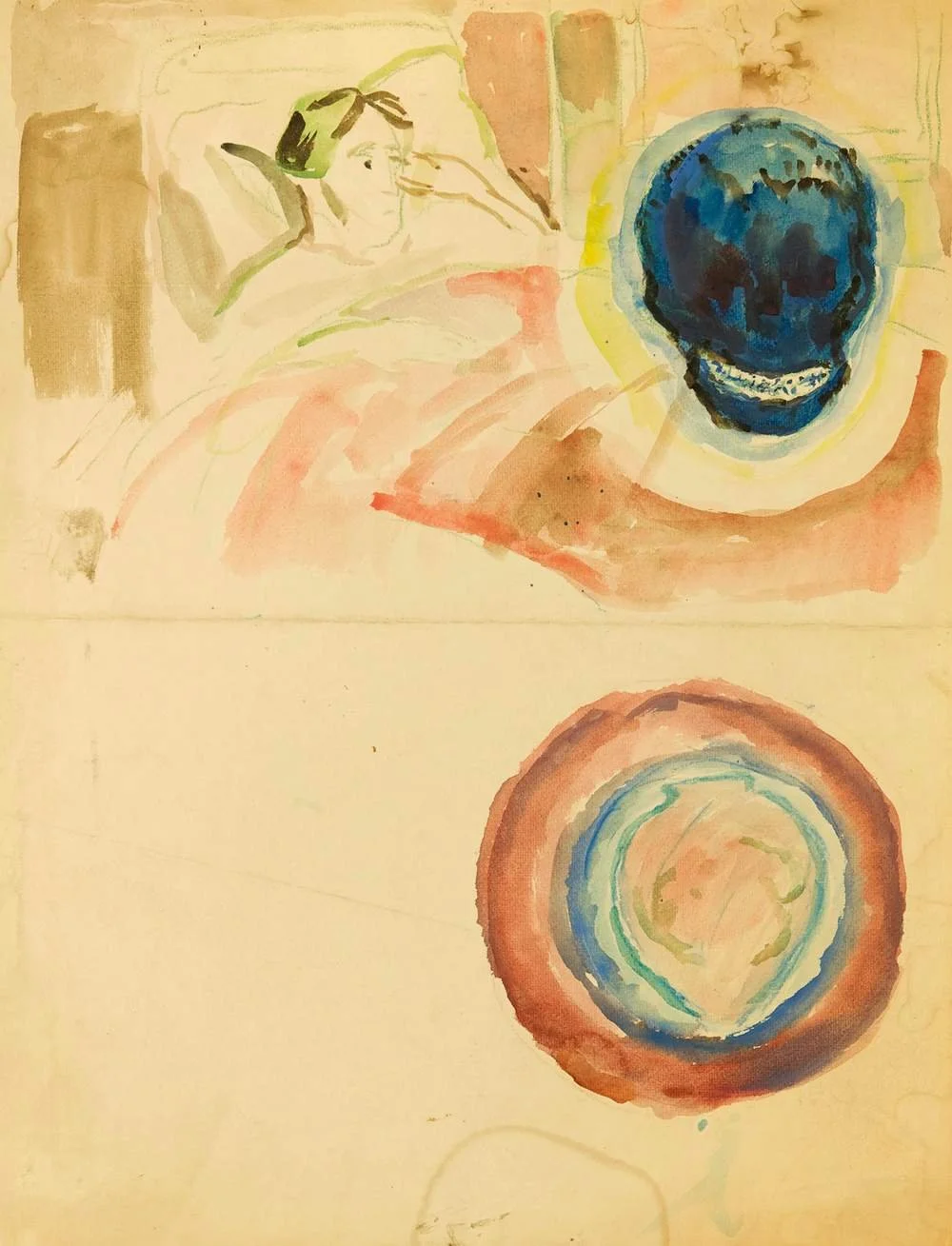

Abstract zig-zag lights resembling ocular migraine aura, symbolizing how the brain shapes visual perception.

Most people think that seeing happens in the eyes. Light enters, the eye focuses, and the image appears. Simple. But the real story of vision is stranger than that. Our eyes collect information, yes—but the brain does the heavy lifting. It edits, organizes, fills in gaps, and sometimes invents. And every so often, the system glitches in ways that can be terrifying, beautiful, or both.

I know this because I suffer from ocular migraines. They’re not ordinary headaches. They’re episodes when the brain itself takes over sight, as if it has its own way of seeing.

The first time, I saw flickering lights around the edges of my vision—like prisms catching sunlight. Another time, a circle of gray swallowed the center of my sight. If I looked at a face, it was blurred out the way television used to censor identities. The strangest episode was when I suddenly saw six separate screens—like floating televisions—each playing what looked like a video. I couldn’t see around them. They moved independently, and it even felt like each eye was working on its own. It frightened me so much I screamed.

As unnerving as they are, these episodes remind me that sight isn’t just about clarity. It’s about perception. And artists have long worked from unusual forms of perception.

Chuck Close had prosopagnosia, or face blindness. He couldn’t recognize people, yet he built his entire career painting portraits. By breaking down a face into grids, tones, and shapes, he made recognition possible through art.

Wassily Kandinsky likely had synesthesia, experiencing sounds as colors and colors as sounds. His paintings feel like orchestral scores—visual music born of cross-wired senses.

Edvard Munch suffered a hemorrhage in his eye and sketched exactly what he saw: blind spots, flashes, distortions. In a sense, his retina became both subject and canvas.

Hilma af Klint described her visions as spiritual downloads. Today, we might call them altered states of perception, but either way, she trusted them enough to build an entire body of radical, visionary work.

For me, ocular migraines are fleeting, but they underscore something essential: we don’t just see with our eyes. We see with our whole nervous system—our histories, our quirks, our anomalies. Vision is never neutral. It’s personal, fallible, and sometimes revelatory.

SCIENCE SIDEBAR: WHAT’S REALLY HAPPENING IN AN OCULAR MIGRAINE?

Doctors believe ocular migraines begin in the brain’s visual cortex, where blood vessels briefly constrict and then relax. This change alters the flow of blood and oxygen, disrupting how signals are processed.

That’s why the disturbances are so vivid: zig-zag lights, kaleidoscopic colors, blank patches, or even floating “screens.” They usually last 20–30 minutes and then vanish as mysteriously as they came.

Ocular migraine: temporary visual glitches caused by brain activity, not by damage to the eyes.

Synesthesia: a neurological trait where senses merge (hearing colors, tasting shapes).

Hallucination: a perception without any external input, usually linked to illness, stress, or drugs.

Each condition is different, but all remind us: what we see is never a simple mirror of reality. It’s an interpretation, a construction. And sometimes, when the brain sees, we glimpse just how creative that process really is.