LOOKING WITH ROGER FRY

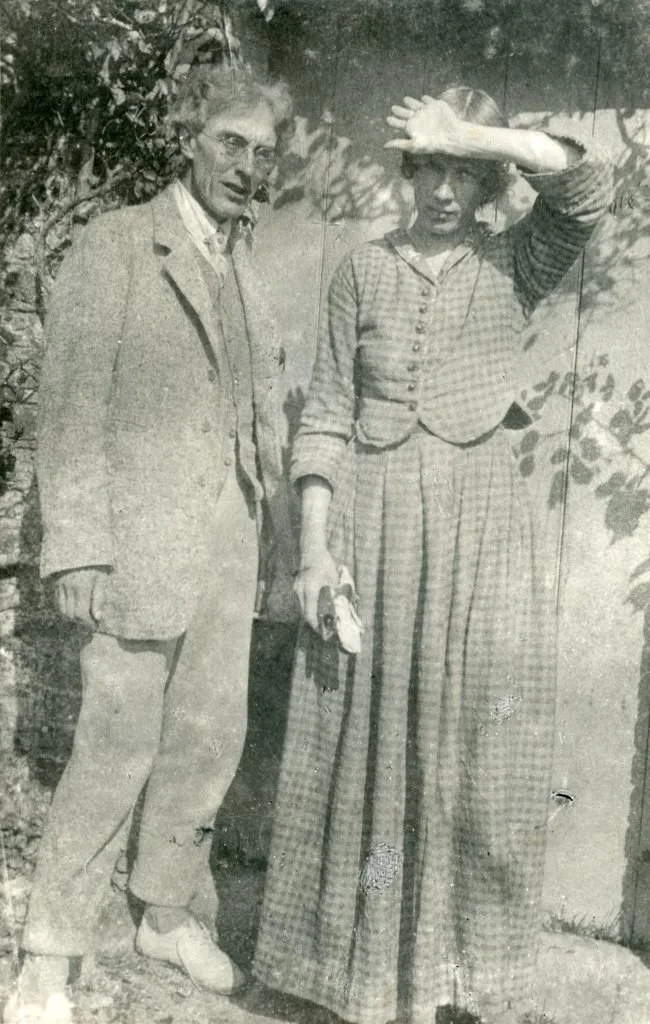

Roger Fry and Vanessa Bell

The first time I read Roger Fry, my immediate thought was: finally, someone who looks at a painting the way I do. Not emotionally first, not narratively, not in search of reassurance or uplift, but through a disciplined form of attention. What we now call formalism felt, in his writing, less like a theory than a discipline—a way of agreeing to stay with what is actually there. Fry’s focus on line, color, rhythm, and spatial structure was not a narrowing of meaning but a refusal to dilute it. He trusted that if you gave yourself fully to the visual problem a painting posed, meaning would arise from the work itself rather than being brought in from elsewhere. Reading him, I felt recognized, not as a believer in doctrine, but as someone committed to looking long enough for perception to organize itself.

Fry is often positioned as a kind of facilitator within Bloomsbury: indispensable, intellectually rigorous, but emotionally peripheral. He loved Vanessa Bell deeply and without reciprocity, and his attachments, like many within the group, were asymmetrical. Yet this distance may have been what allowed him to see so clearly. Where others lived the experiment of Bloomsbury through relationships, Fry articulated its visual intelligence. He was less interested in how one ought to live than in how one might learn to look.

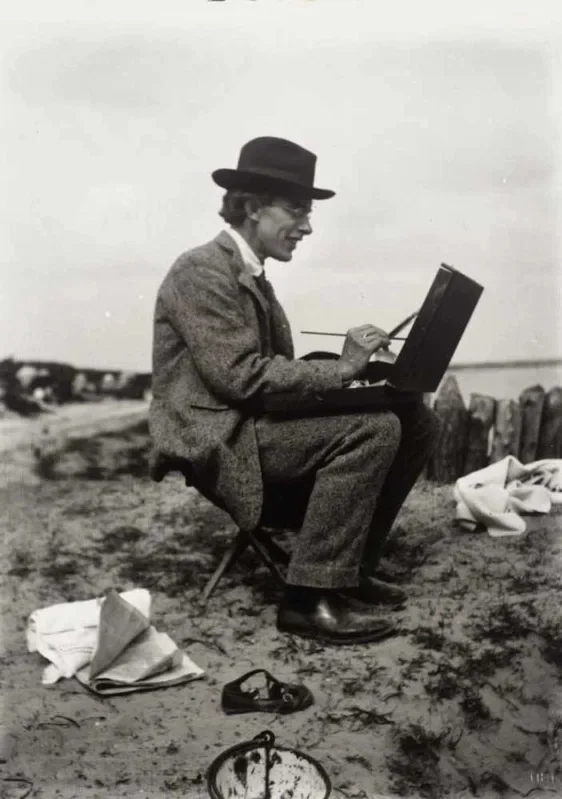

Roger Fry Painting

What he offered, above all, was a way of placing attention. His writing does not instruct you what to feel in front of a painting; it asks you to notice what is doing the work. In essays such as An Essay in Aesthetics and in his criticism of Post-Impressionism, Fry redirected English audiences away from subject matter and toward form—not as decoration, but as structure. Line, mass, and color were not secondary to meaning; they were how meaning came into being. This was a subtle but profound shift. Painting was no longer a vehicle for ideas formed elsewhere. It became a site where thought could happen visually.

His writing on Paul Cézanne makes this argument with particular force. Fry understood that Cézanne was not simplifying nature, nor distorting it, but reconstructing it through perception. Mont Sainte-Victoire appears again and again not because Cézanne had exhausted invention, but because he was engaged in sustained inquiry. Each canvas tested how weight settles, how color advances or recedes, how space coheres without relying on illusion. Fry saw that these paintings were not offering images of certainty but records of thinking—seeing made visible as process rather than conclusion.

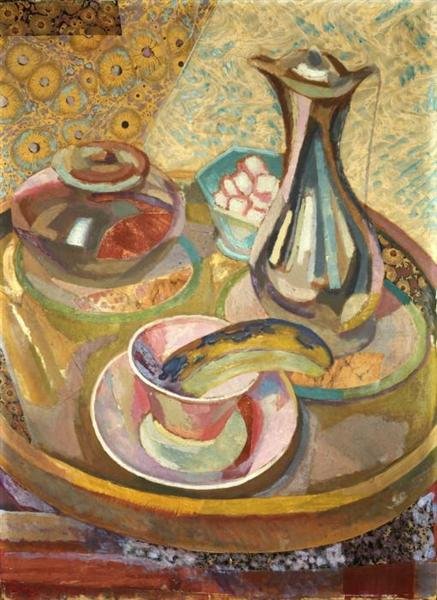

Roger Fry, Still Life with Coffee Pot

This way of looking was radical at the time, and it remains demanding now. It requires patience, a tolerance for ambiguity, and a willingness to let perception lead rather than follow explanation. Fry understood that once you accept form as a primary site of meaning, you cannot go back to looking casually. Attention becomes a commitment. Relationships—between colors, between shapes, between parts of a painting—are provisional, negotiated, and held together only as long as they remain convincing.

It is not difficult to see how this visual logic extended into the lives around him. Bloomsbury’s emotional arrangements were rarely stable and seldom resolved, but they were attentive. They required negotiation, revision, and a refusal of easy closure. Fry may not have lived the most flamboyant version of that experiment, but he gave it its clearest grammar. He taught a generation of artists and viewers to trust looking itself—to understand connection not as something fixed, but as something continuously made through sustained attention.

Roger Fry: A Selected Reading List

Vision and Design

Start here.

This is the book artists still recognize themselves in. Read selectively, not cover to cover. Fry teaches you how to place attention—on line, weight, rhythm, and spatial tension—without turning form into dogma. Think of it as studio thinking put into language.

Cézanne: A Study of His Development

Essential if you care about repetition, structure, and inquiry. Fry understands Cézanne as someone working a problem rather than producing images. This is a book about staying with looking.

Transformations

A quieter, slightly looser companion to Vision and Design. Less polemical, more reflective. Good to dip into when you want to think about how form migrates across time, cultures, and media.

Last Lectures

Optional, but rewarding. These late lectures feel closer to conversation than argument. Fry sounds less like a critic and more like a seasoned observer clarifying what matters after a lifetime of looking.