VANESSA BELL: LIVING THE TRUTH

Vanessa Bell did not set out to be radical. She set out to live honestly. The radicalism followed.

She believed that the way one lived mattered as much as the work one made, and that conventions—marriage, propriety, feminine self-effacement—were only useful if they did not interfere with the truth of daily life. When they did, she quietly stepped around them.

This was not a theory. It was practice.

Marriage, Reconsidered

Vanessa married Clive Bell young, before she fully understood the terms being offered. Clive was brilliant, articulate, devoted to art and ideas, and deeply unsuited to exclusivity. Rather than dismantle the marriage when it no longer worked in a conventional sense, Vanessa refused the premise that marriage had to be dismantled at all.

They stayed married. They raised children. They loved other people.

Clive remained part of the household, intellectually and emotionally, even as Vanessa fell deeply and irrevocably in love with someone else. This arrangement baffled and offended many, but it was not careless. It was negotiated, lived into, adjusted. Vanessa was not rejecting marriage so much as refusing to let it dictate the shape of her emotional life.

For her, marriage was not a moral endpoint. It was one structure among many, and not necessarily the most important.

Duncan Grant, Self-Portrait

That love was Duncan Grant.

Their relationship did not conform to any easy narrative. Duncan was bisexual, often involved with men, sometimes inattentive, frequently difficult. Vanessa knew this from the beginning. She did not ask him to be someone else. She asked only that he remain present.

They lived and worked together for decades. They painted side by side. They raised a child together. They argued. They disappointed one another. They stayed.

What held them was not romance in the sentimental sense but something steadier: shared attention, shared work, shared space. Vanessa understood that love could survive contradiction, and that devotion did not require ownership.

When she died, Duncan said simply that he could have been kinder to her. The sentence contains an entire life.

Interior of Charleston, more extraordinary pictures here

Charleston: A House Built on Belief

Charleston, the farmhouse in Sussex where Vanessa and Duncan settled during the First World War, was not meant as a utopia. It was meant as a place where life and work could coexist without apology.

The walls were painted. The furniture was painted. Doors, mantels, cupboards—nothing was neutral. Art was not reserved for canvases; it spilled into the structure of the house itself. Living space became studio. Studio became domestic. There was no hierarchy between the two.

Charleston was also a social experiment. Children, lovers, friends, former spouses moved in and out. Meals were shared. Arguments unfolded. Work continued.

What made it function was not permissiveness but seriousness. Vanessa took the labor of living together as seriously as the labor of painting. That, more than the decor, was the innovation.

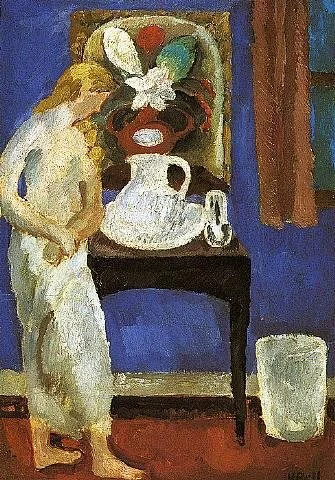

The Blue Room, Wissett Lodge, by Vanessa Bell

The Work: Seeing Without Ornament

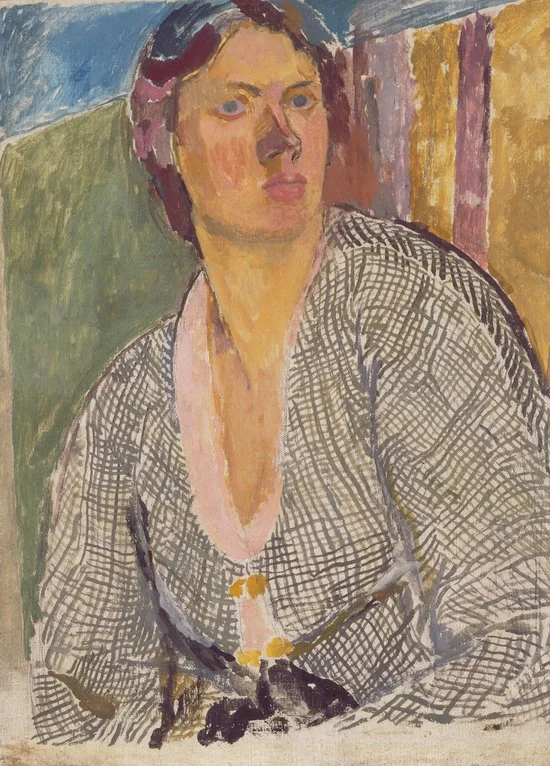

Vanessa Bell’s painting is often described in relation to others—Roger Fry, Duncan Grant, Cézanne, Matisse—but her distinctiveness lies in restraint. She resisted drama. She preferred structure, pattern, balance. Her interiors and still lifes hold tension quietly. Her figures do not perform. They occupy space.

She was not interested in spectacle. She was interested in how things actually look when you live with them.

That sensibility carried into everything else she did. Vanessa did not aestheticize her life; she lived it plainly and allowed form to emerge. The paintings follow that ethic. They do not insist. They endure.

Virginia Woolf by Vanessa Bell c.1912 ( © Estate of Vanessa Bell, courtesy Henrietta Garnett)

Her sister, Virginia Woolf, lived the same commitment differently. Where Virginia interrogated experience through language, Vanessa absorbed it through looking. Virginia worried at meaning; Vanessa arranged it.

They were close, competitive, mutually formative. Virginia admired Vanessa’s steadiness. Vanessa protected Virginia’s fragility without condescension. Each provided something the other lacked.

Virginia once wrote of staying at Charleston, of the painted walls and the sounds of the countryside pressing in at night. What she recognized there was not just a house but a way of being: art embedded in daily life, without explanation.

Vanessa Bell did not write manifestos. She lived an argument.

That argument was simple and difficult: tell the truth about what you need, what you love, what you can sustain. Build a life that can hold those truths without pretending they are tidy. Accept the costs without dramatizing them. Keep working.

In a world that still confuses convention with virtue, Vanessa’s life remains quietly instructive. She shows that integrity is not about purity. It is about coherence.

Charleston stands because she believed that how we live is not separate from what we make. The paintings endure because she trusted that attention, applied patiently, is enough.

Everything else was negotiable.

Written with the help of AI