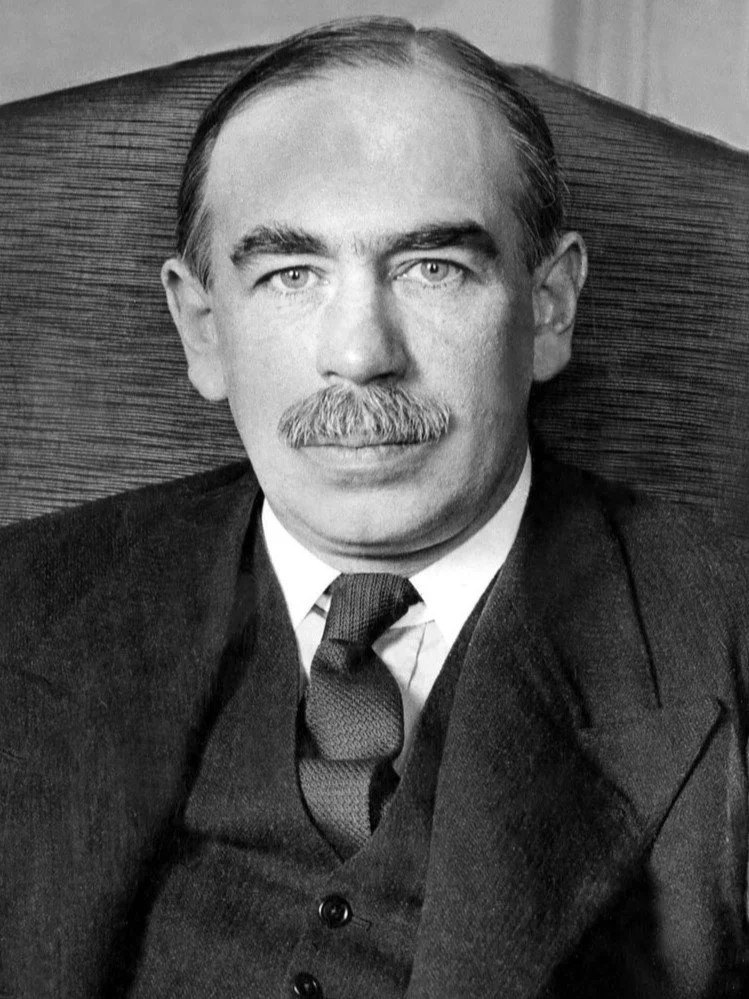

JOHN MAYNARD KEYNES: Economics with a Nervous System

John Maynard Keynes is usually introduced as the economist who saved capitalism from itself. That is true, as far as it goes. But it is not how he thought of himself, and it is not how he lived.

Keynes moved through the world less like a technocrat than like a man attentive to atmospheres—rooms, moods, confidences, collapses. His economics emerged not from abstraction, but from observation: how people actually behave when frightened, hopeful, reckless, bored. He did not believe that markets were rational systems tending naturally toward equilibrium. He believed they were made of people, and that people were volatile, suggestible, contradictory, and emotional.

That one shift, treating economic life as a psychological field rather than a mechanical one, changed everything.

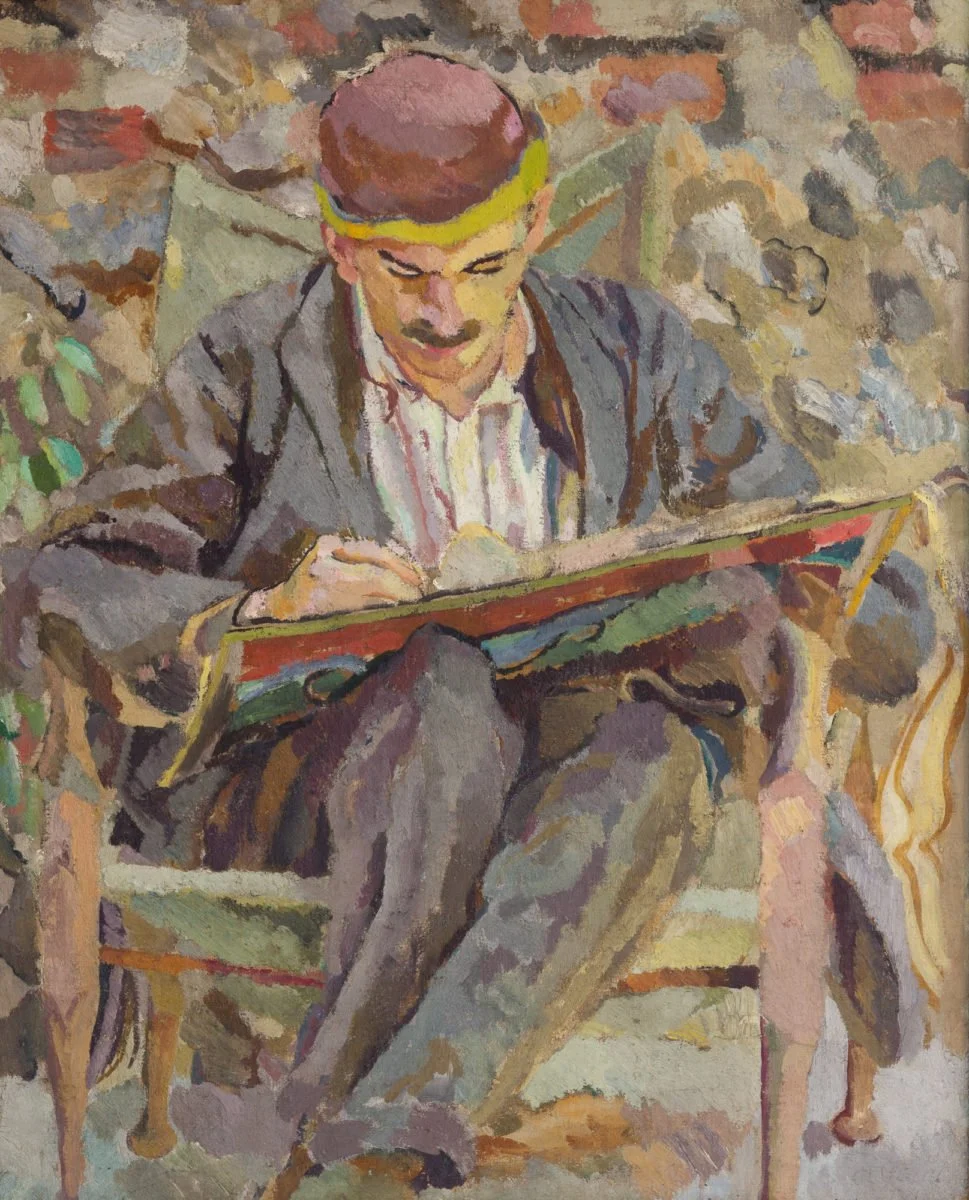

Maynard Keynes by Duncan Grant

Keynes gave us language that we still use because it describes something real we recognize in ourselves.

Animal spirits.

This is the phrase everyone remembers, often without remembering what it means. Keynes used it to describe the non-rational forces that drive economic decisions: confidence, fear, optimism, panic. Investment, he argued, is not the outcome of calculation alone. It is an act of nerve. When animal spirits collapse, money stops moving, not because the numbers no longer add up, but because belief drains out of the system.

You can see this instantly in a studio or in a gallery during a downturn. Nothing is “wrong,” exactly. But no one is buying. The energy has gone flat.

The paradox of thrift.

Common sense says that saving is virtuous. Keynes pointed out that if everyone saves at once, demand collapses, businesses fail, and unemployment rises. What is prudent for the individual becomes destructive at the collective level.

This idea is deeply Bloomsbury in spirit: the refusal of moralism in favor of structural thinking. Keynes was not asking whether thrift was good or bad. He was asking what happens.

Sticky wages and prices.

Keynes understood that wages and prices do not adjust smoothly or instantly, no matter how elegant the theory. People resist pay cuts. Institutions lag. Pride intervenes. Habit intervenes. Time intervenes.

This sounds obvious now. It was not then. It was a direct challenge to the fantasy of frictionless systems.

Demand matters.

This is the core of Keynesian economics and the reason he mattered so much during the Great Depression. When private demand collapses, public spending is not a moral failure or an indulgence. It is a stabilizing force. Governments, he argued, should act counter-cyclically—spending when others cannot or will not.

Keynes was not sentimental about this. He was practical. People without jobs cannot buy goods. Economies do not heal themselves through patience alone.

Keynes did not arrive at these ideas in isolation. He was formed inside the social and intellectual environment of the Bloomsbury Group.

Bloomsbury distrusted inherited authority. They were suspicious of grand systems that ignored lived experience. They valued conversation, intimacy, and contradiction. They believed that private life and public life were inseparable, and that ideas were shaped in rooms, not just in books.

The Bloomsbury Group.

Keynes’s early relationships—with Duncan Grant, Lytton Strachey, and others in the circle—were intense, emotionally charged, and intellectually formative. These were not casual affairs. They were relationships conducted at full voltage, with arguments about art, ethics, pleasure, and responsibility unfolding alongside desire.

Keynes never separated feeling from thinking. He did not believe that intellect operated best in a vacuum. He believed it operated best when fully exposed to human complexity.

Keynes with Lydia Lopokova

His early love affairs were with men; later, he married Lydia Lopokova, a ballerina whom many of his Bloomsbury friends initially dismissed as unserious. They were wrong. Lydia grounded him. She brought a physical intelligence and theatrical sense of timing into his life that complemented his own sensitivity to rhythm and momentum.

Keynes understood cycles, not just economic ones, but emotional ones. He understood anticipation, delay, exhaustion, and recovery. These are not abstract concepts. They are lived states.

Bloomsbury’s Influence: Ethics Without Piety

Bloomsbury was shaped by the philosopher G. E. Moore, who argued that the good consisted of states of mind: friendship, love, and aesthetic experience. This framework freed them from conventional moral hierarchies while placing enormous responsibility on honesty and attentiveness.

Keynes absorbed this deeply. His economics is not value-neutral. It is grounded in a belief that mass unemployment is not merely inefficient but ethically intolerable. That wasted lives are not acceptable collateral damage in the pursuit of theoretical purity.

He once wrote, during the aftermath of the First World War, that he worked “for a Government I despise for ends I think criminal.” That sentence is often cited for its political content. It is equally revealing psychologically. Keynes was not interested in allegiance for its own sake. He was interested in consequences.

We live in a moment when markets are again treated as omniscient, and public intervention is framed as weakness. Keynes would have recognized this mood instantly. He would have called it a triumph of superstition over observation.

He did not believe that markets were evil. He believed they were fragile. He believed they required care, maintenance, and occasional intervention, not unlike other complex systems involving human beings.

Keynes’s greatest contribution was not a formula. It was permission: permission to acknowledge uncertainty, to act in the face of incomplete knowledge, to value stability over purity.

For an artist, this is familiar terrain. You begin without knowing how the painting will resolve. You proceed anyway. You adjust. You respond to what is actually there, not what theory says should be there.

Keynes understood that economies, like paintings, are not solved. They are managed, revisited, and lived with. They require judgment, not just calculation.

That sensibility, the refusal of false certainty, the insistence on attending to human behavior as it actually unfolds, is Bloomsbury’s quiet legacy inside modern economics.

And it remains, inconveniently, correct.

Written with the help of AI.