STUDIO NOTES — JANUARY

TABLES, BARS AND THE ARCHITECTURE OF POWER

As we rang in the New Year, I found myself thinking about how people gather. Who is welcome. Who is watching. And, inevitably, who is paying.

That line of thought sent me straight down a rabbit hole. I started with the cafés of 19th-century Paris, which functioned less as places to eat than as unofficial social clubs for the Impressionists. From there I moved to the watering holes of New York artists in the last century, where ideas were tested, alliances formed, and reputations occasionally dismantled over a drink.

Having grown up during the Vietnam War, I couldn’t stop there. I remember how much diplomatic labor took place around tables—literal tables. When negotiations with North Vietnam stalled over something as basic as the shape of the negotiating table, someone—Henry Kissinger, I assume—floated the idea that talks should take place at a cocktail party instead. Everyone standing. Everyone milling. No hierarchy implied by seating. The suggestion alone revealed how much power lives in arrangement.

From there, the trail widened: Nixon in China. De Gaulle at the White House. And eventually, the most accomplished food diplomat of them all, Louis XIV, who understood better than anyone that meals are never just meals.

January’s Studio Notes follows that path: from cafés and bars to banquets and negotiating tables, tracing how art, power, and influence tend to reveal themselves when people sit down together—or don’t.

ARTISTS, BARS, AND THE SOCIAL LIFE OF ART

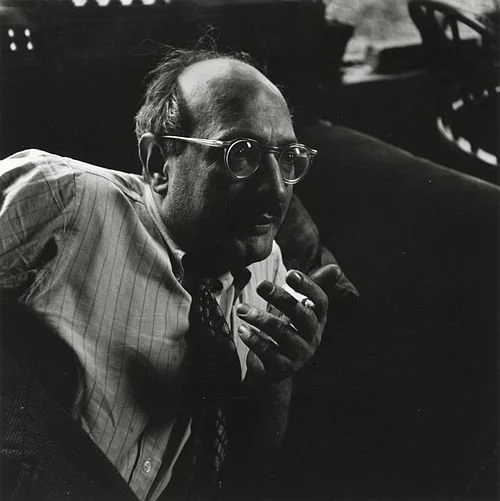

I never lived in New York City, but when I visited artist friends, we’d inevitably drift to the Spring Street Bar, where other artists seemed to appear as if summoned. Someone would buy a drink. Someone else would mention a new piece. And often, we’d head back to a studio to look at work.

In SoHo at that time, the bar functioned as a kind of social lubricant for the neighborhood. It wasn’t really about drinking so much as circulation—of people, ideas, and information. It was where you caught up, tested a thought out loud, or figured out what was happening two blocks over. Work was discussed. Introductions were made. Futures were sketched on the backs of napkins.

But those rooms had gravity. For some people, they were energizing, even stabilizing—a place to belong, to measure oneself against others. For others, the pull was stronger, harder to escape. Put enough creative people together, and some ignite, while others quietly burn out. That’s part of the history, too.

NEW THIS MONTH:

THE IMPRESSIONISTS AT TABLE: WHERE THEY ATE, WHO PAID, AND WHY IT MATTERED

Few things reveal the inner life of artists more than where they choose to eat once they finally have a franc in their pockets. For the Impressionists, dining was never simply sustenance—it was strategy, camaraderie, theater, and the occasional act of defiance. Their restaurants tell the story of their rise: from noisy cafés of argument to polished dining rooms where turbot arrived under silver domes.

NEW YORK CITY : ARTIST, BARS AND THE MAKING OF A SCENE

New York has always had two art worlds: the one in the studios and the one at the bar. The former produced the work; the latter produced the legends. If Paris had its cafés, New York had its dimly lit rooms with sticky floors, cheap whiskey, and artists who argued, seduced, collapsed, and occasionally painted the bathrooms. Stroll through the great artist bars of New York City — who drank where, who paid, what they ordered, and what survives.

READ MORE . . .

THE HANGOVER

Every story about artists and bars eventually needs a morning-after chapter. This is it.

It’s tempting to treat drinking as part of the atmosphere, like bad lighting or loud music. Something incidental. Something that belongs to the room rather than the body. And for a while, it does. Conversations loosen. Arguments sharpen. People stay later than they should. Work gets talked about intensely, if not always made. But alcohol is not neutral. It never was.

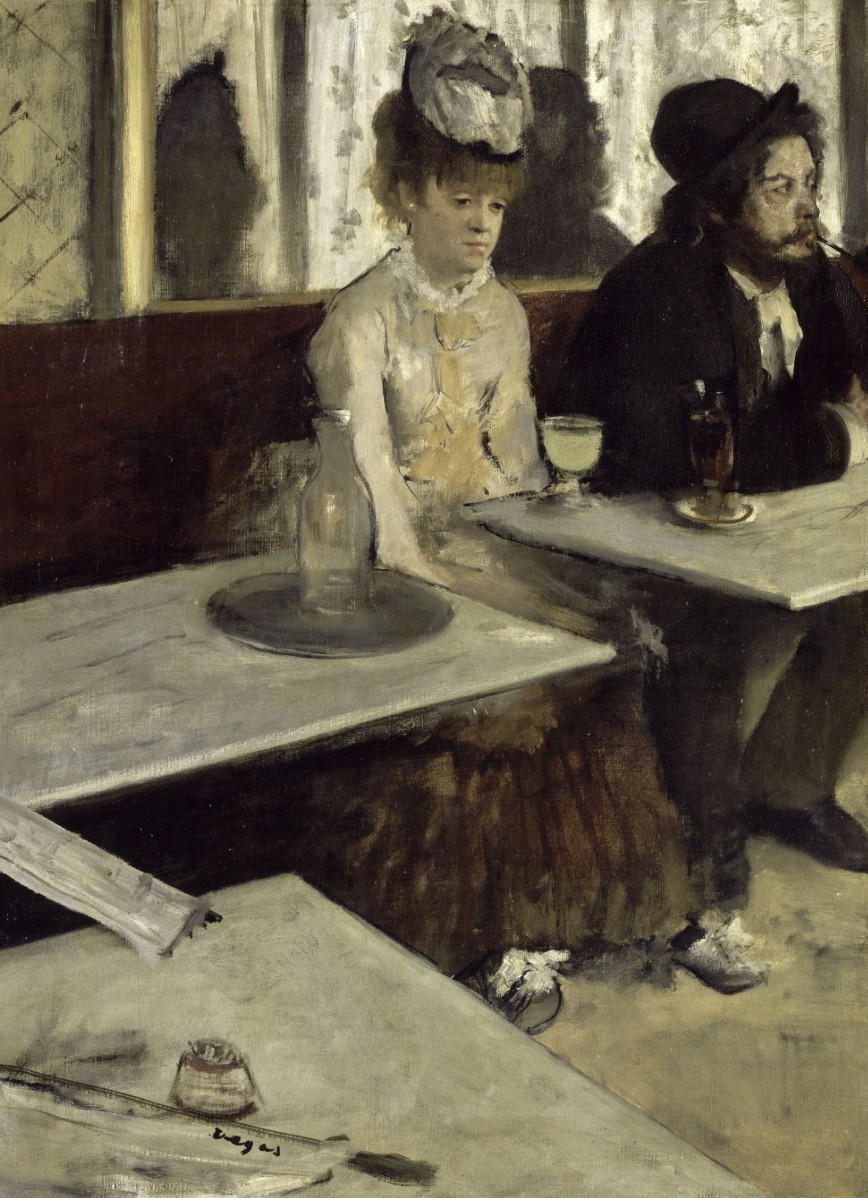

HISTORY SPOTLIGHT: Dégas’ The Absinthe Drinker

Degas’s L’Absinthe is less a painting about drinking than a painting about aftermath. Two figures sit at a café table, close enough to touch, yet sealed off from each other and from us. The woman stares past her glass, not lost exactly, but emptied out. The man turns away, already disengaging. Nothing dramatic is happening, which is precisely the point. Degas doesn’t give us bohemia or bravado. He gives us the long middle of things: fatigue, isolation, and a room that no longer offers relief. When it was exhibited, viewers were scandalized—not because of excess, but because they recognized the mood. This is the café after the conversation has stalled, when the drink remains but the reason for it doesn’t. It’s a painting that refuses the romance and leaves you sitting with the cost.

FOOD, POWER, AND POLITICS

The second half of this month’s reading shifts from artists to heads of state, but the logic remains the same. Power likes a table.

Whether it’s Louis XIV dining in public at Versailles, Nixon navigating banquets in China, or modern leaders staging photo-op meals, food has long functioned as soft power—ceremony, choreography, signaling. What is served, who sits where, who speaks, who watches. None of it is accidental.

If you’ve ever wondered why a contemporary president might feel compelled to add an enormous gilded ballroom to the White House, the answer isn’t hard to find. Louis XIV solved that problem centuries ago.

NEW THIS MONTH:

FOOD DIPLOMACY: HOW MEALS HAVE SHAPED WORLD POLITICS

History is full of treaties written in ink—but many were sealed in sauce. "Food diplomacy" may sound quaint, but it has altered borders, changed empires, soothed enemies, and occasionally humiliated them. The table has always been a stage, and the meal a weapon or an olive branch. From Carême’s diplomatic cuisine to modern photo‑op hamburgers, the evolution of political dining tells us exactly how power works—and how it tastes.

THE SUN KING AT SUPPER: HOW LOUIS XIV TURNED DINING INTO POWER

If you have ever walked into a fine restaurant and felt a little smaller, a little more aware of your posture, or a bit uncertain about your knife, you may be experiencing the long shadow of Louis XIV. The Sun King did not invent haute cuisine to delight the palate. He created a world in which eating was a political act. The food was beautiful, but the real purpose was control.

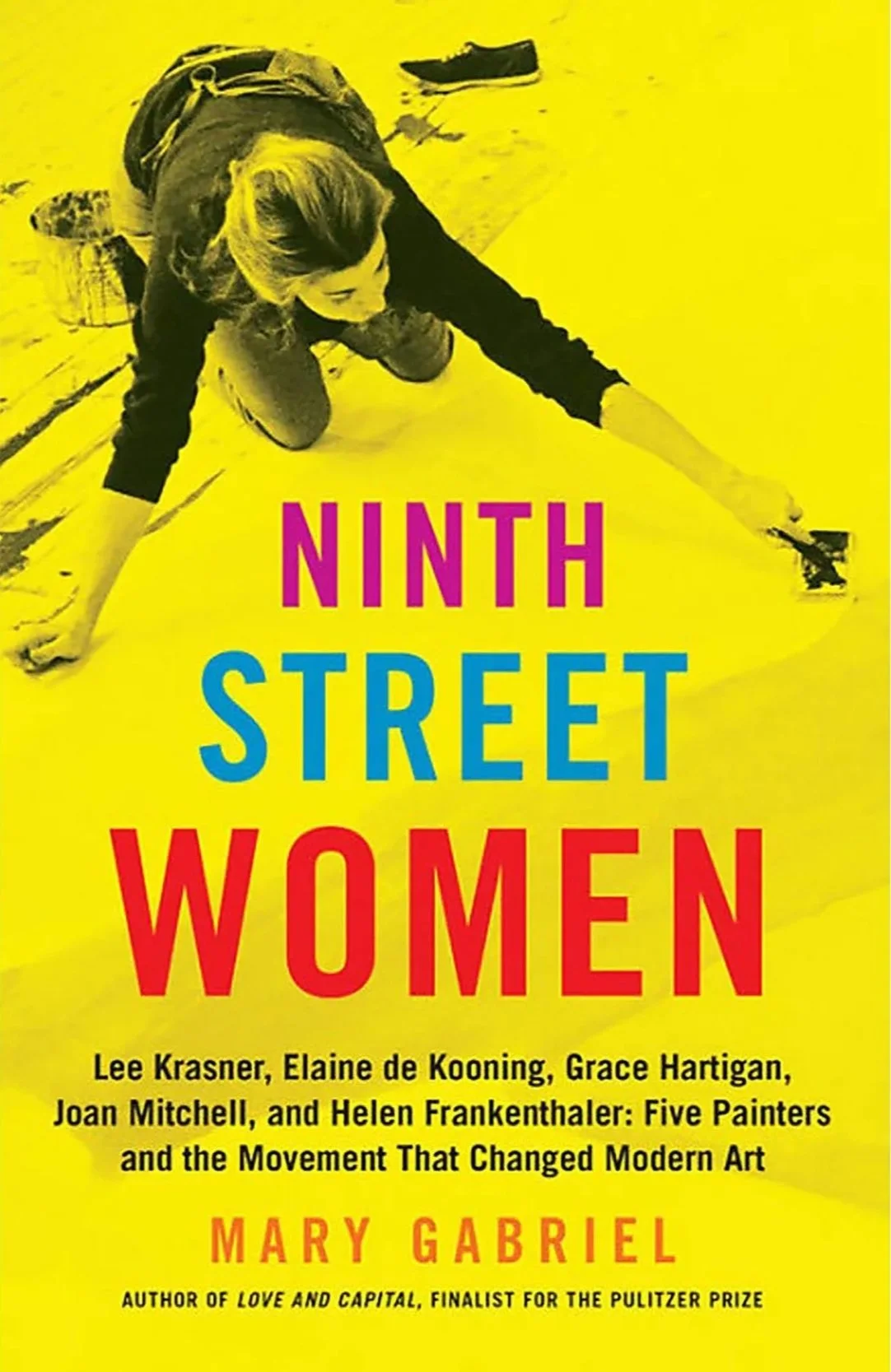

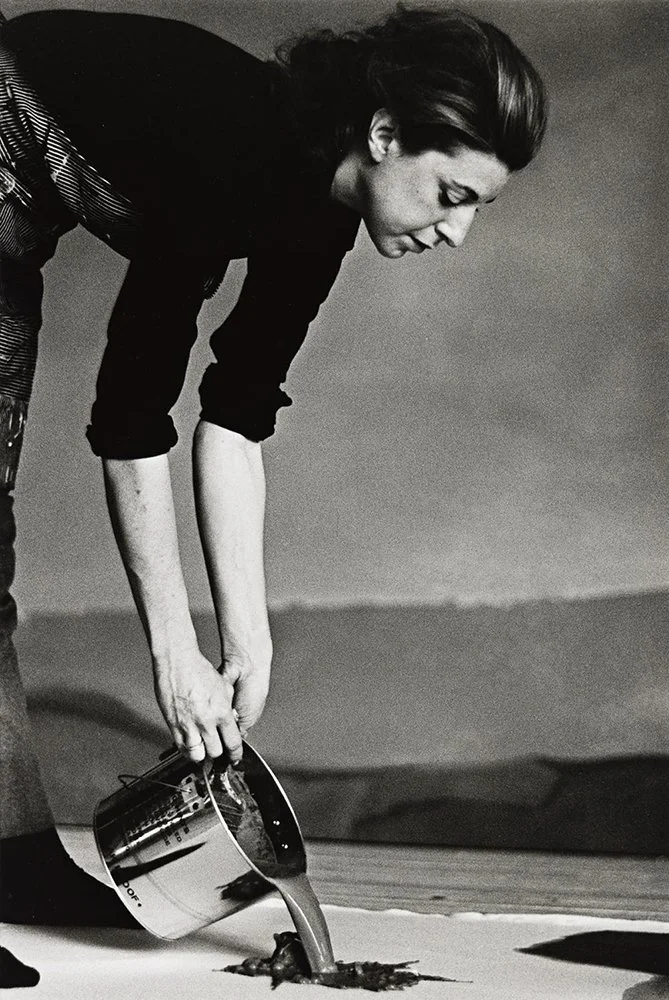

FROM THE LIBRARY: Ninth Street Women by Mary Gabriel

A bracing corrective to the heroic mythology of Abstract Expressionism. Gabriel’s book restores the women—Lee Krasner, Elaine de Kooning, Grace Hartigan, Joan Mitchell—to their rightful place in the story, without romanticizing the costs of proximity to genius. Read it alongside the bar stories for a fuller picture of who paid, who endured, and who was written out.

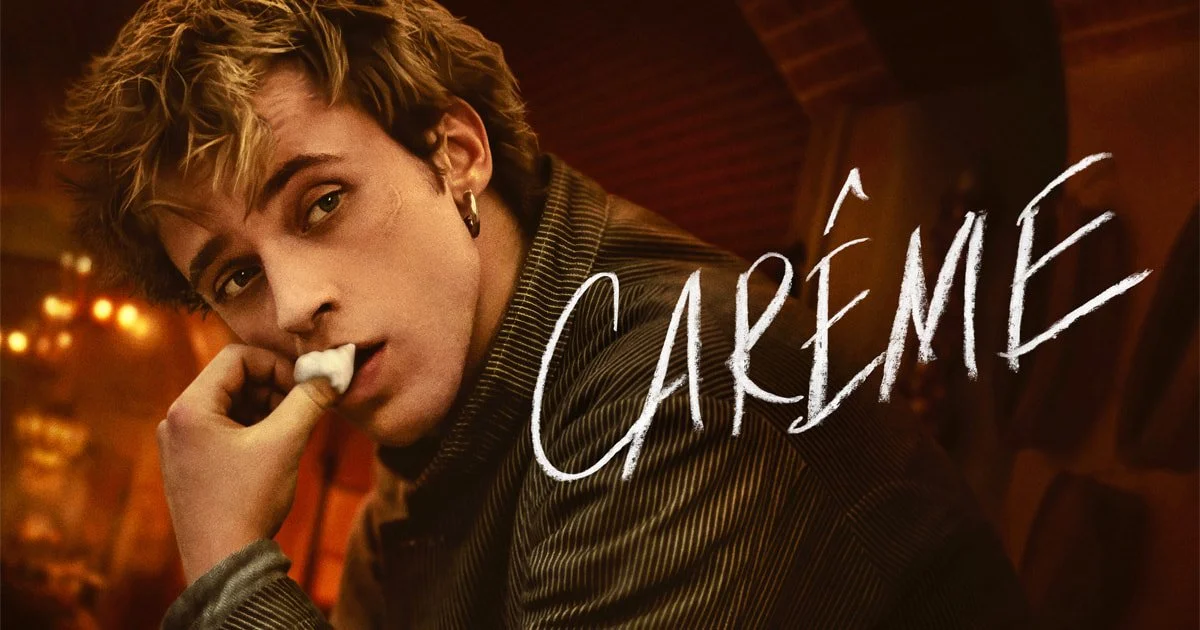

ON SCREEN: Carême

Carême is a lavish historical drama that reimagines the rise of Marie-Antoine Carême, the first celebrity chef, as a story of ambition, beauty, and political power. Set in post-Revolutionary France, the series presents Carême not only as a culinary genius but as a man whose food becomes a diplomatic instrument, moving seamlessly between kitchens and corridors of power. Through his relationship with Talleyrand, cooking is framed as strategy: pastries and sauces operate as persuasion, seduction, and leverage in a volatile Europe being reshaped after Napoleon. Visually sumptuous and deliberately modern in pacing, Carême treats cuisine as architecture and performance, showing how refinement, spectacle, and appetite became tools of statecraft long before public relations had a name.

FEATURED ART: ABOUT THIS TABLE

That’s January: rooms full of people, tables set with intention, conversations that mattered—and the quieter reckonings that followed.