December Notes - 2025

THE GREAT ACTS OF GIVING

Artists, collectors and communities who keep the work alive.

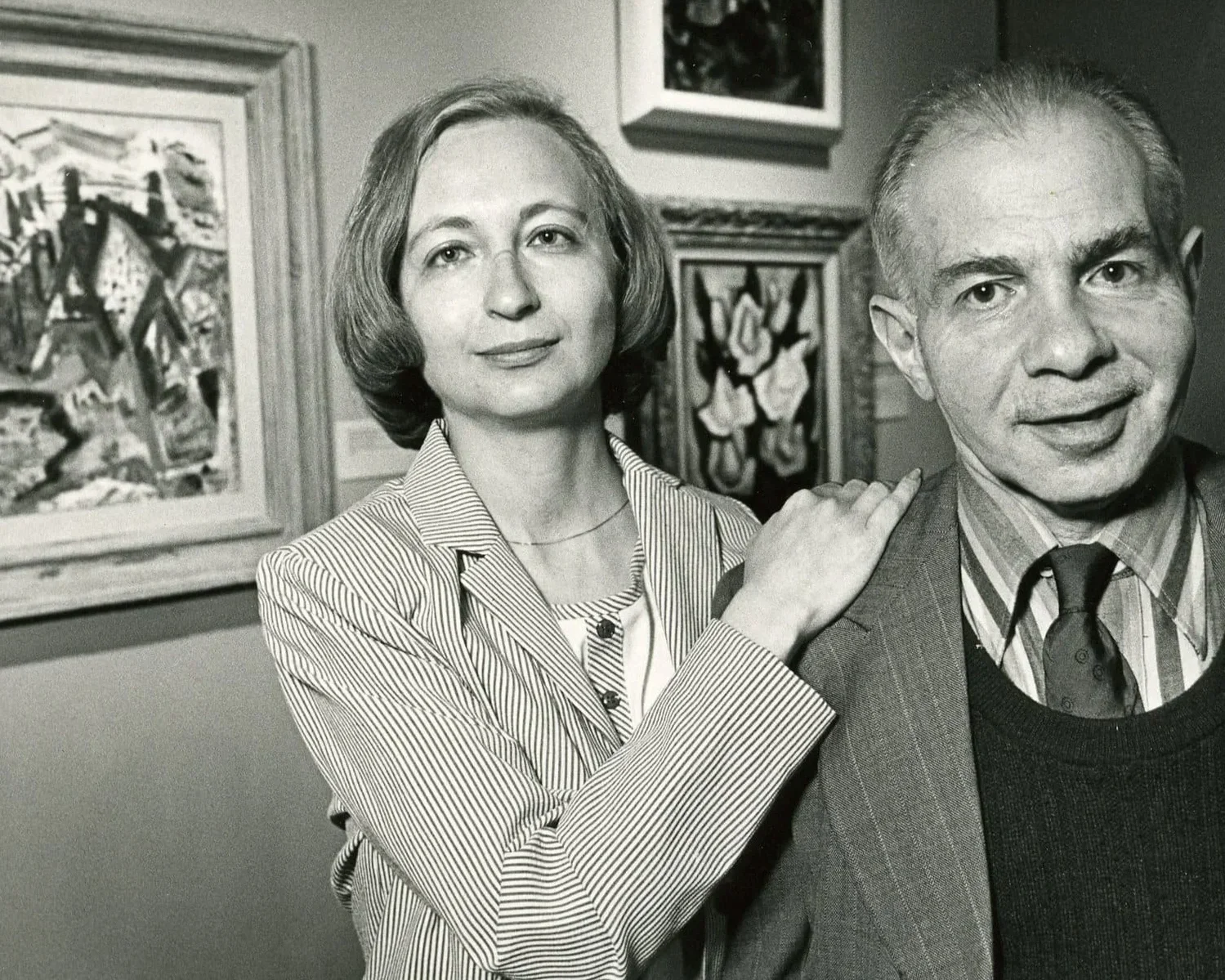

Dorothy Vogel died in November. Her obituary was short, an elderly woman, a retired librarian, but the life behind it was monumental. She and her husband, Herb, a postal clerk, built one of the most important collections of contemporary art on two modest salaries. And then they gave it all away.

The Vogels understood something essential: art survives because someone chooses to carry it forward. That act can be dramatic or quiet, public or private, grand or almost invisible. It can look like a foundation, or a tube of paint passed from one studio to another. It can look like a collector giving thousands of works to museums, or a neighbor bringing food.

This month, I’ve been thinking about the hands that hold art up -

the artists who build legacies,

the collectors who become stewards,

the small gestures that ripple outward,

and the local institutions that keep culture alive here, where we actually live.

Below are brief reflections on each. I’ve linked them to longer posts if you’d like to go deeper.

ARTISTS WHO BUILT LADDERS FOR OTHERS

Artists don’t often have the luxury of planning for posterity. Yet a handful took the long view, and the art world is different because of it.

Lee Krasner left the bulk of her estate to create the Pollock-Krasner Foundation, one of the most significant sources of funding for working artists today. Robert Rauschenberg built a foundation rooted in collaboration and social imagination. Joan Mitchell established a foundation to support painters and poets — the creative pairings she cared most about. Adolph and Esther Gottlieb created a trust that quietly stabilizes artists in moments of need, especially those well into their careers.

These weren’t ornamental legacies. They were built from memory — from having once been broke, dismissed, or unseen. They institutionalized generosity so that others wouldn’t have to endure what they endured.

They built ladders while climbing them.

Those ladders still stand.

COLLECTORS WHO TURNED OWNING INTO OFFERING

Collectors have always shaped what survives — but a few have done so with unusual integrity.

The Vogels collected art because they loved it, lived with it, and wanted it to be public. Their “Fifty Works for Fifty States” program placed contemporary art in museums across the country, not in warehouses.

Peggy Guggenheim used her resources to help artists escape Europe during the war — an act that saved lives and altered the course of modernism. Later, she built one of the first public homes for contemporary art in Venice.

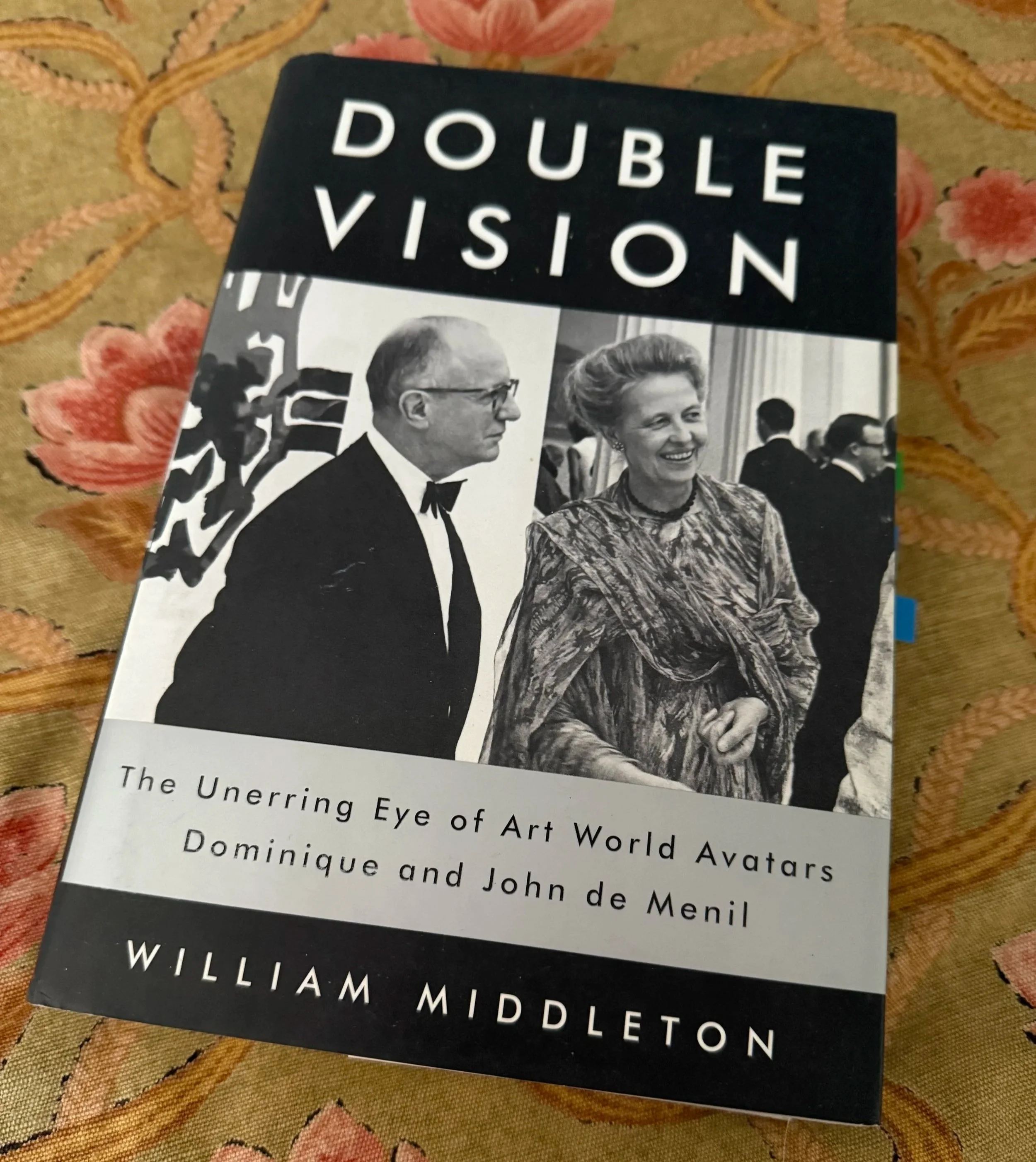

Dominique and John de Menil built museums, exhibitions, and cultural institutions rooted in dialogue, spirituality, and human rights. Their daughter Philippa, with Heiner Friedrich, helped found the DIA Art Foundation — long-term patronage on an almost medieval scale. Artists like Dan Flavin, Donald Judd, and Walter De Maria found stewardship there, not just support.

The Vogels

SMALL ACTS, QUIET ACTS

Not all generosity is institutional. Most of it isn’t.

The small stories travel like folklore:

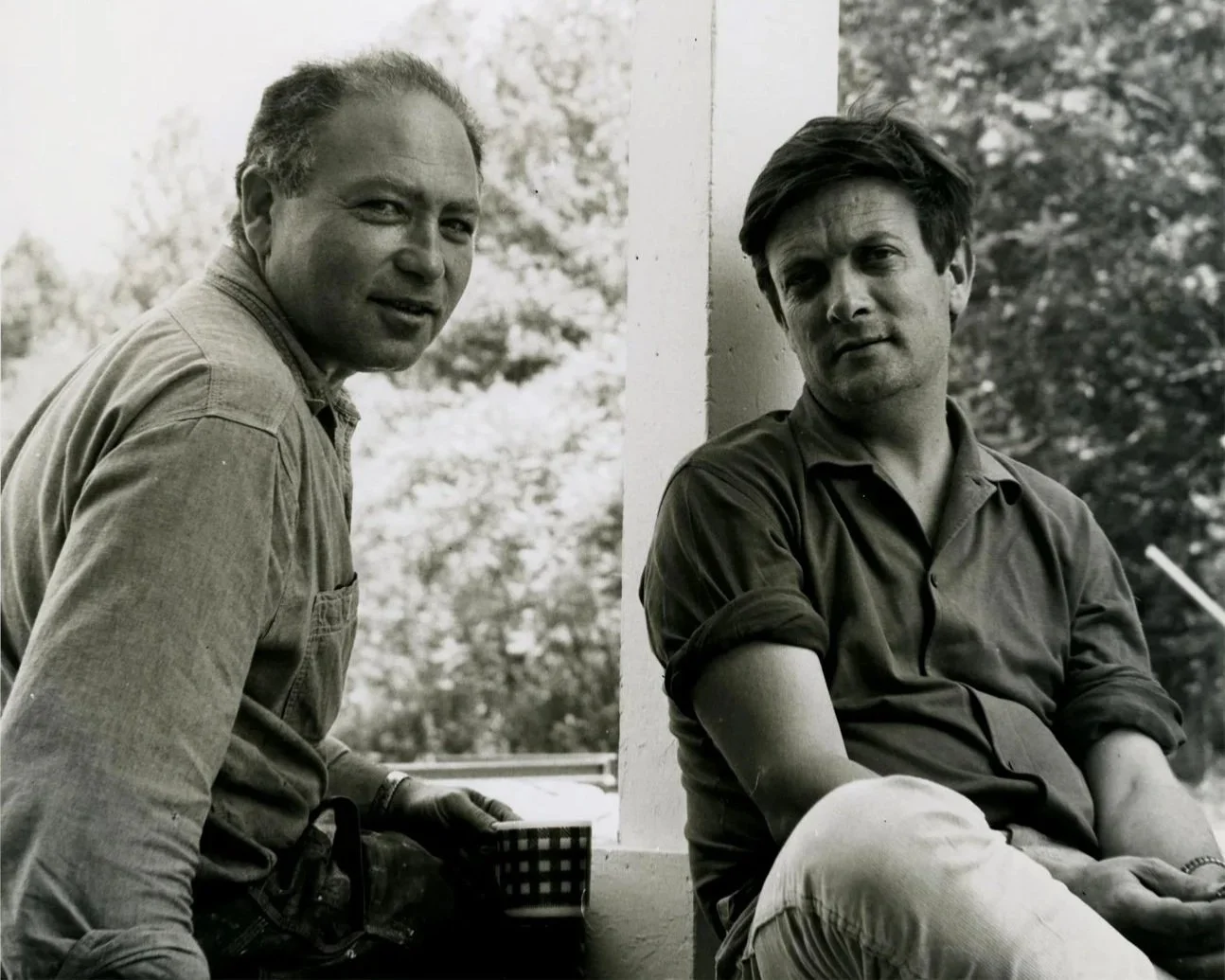

Kenneth Noland bought materials for Jules Olitski when he couldn’t afford them.

Jasper Johns took Lichtenstein’s work to Leo Castelli when Lichtenstein couldn’t bring himself to do it.

Agnes Martin slipped younger artists envelopes of cash in Taos, or simply showed up at their studios with her full attention — maybe the rarest gift of all.

These gestures don’t appear in wall texts, but they’ve shaped as many careers as any museum.

Art is held together by this quiet currency.

And it circulates more freely than we think.

GIVE WHERE YOU ARE

Music from Salem in all its iterations.

Art is sustained not only by foundations and collectors, but by the institutions and organizations in the places where we actually live. Four here matter deeply:

BENNINGTON MUSEUM : A guardian of regional modernism and a home for the unexpected.

HUBBARD HALL : Where community, history, and performance meet, and where I once helped run the Curiosity Forum when people needed free programs most.

MUSIC FROM SALEM : Chamber music as communion, offered with care and intimacy.

COMFORT FOOD COMMUNITY : Because without food, there is no art. Hunger erases possibility.

Supporting these places supports the ecosystem that enables creativity.

It is generosity at the scale of community, not abstraction.

AT THE MOVIES: THE VOGEL LEGACY

Herb & Dorothy: The Art of Collecting (2008)

Directed by Megumi Sasaki

The first film tells the improbable story of Herb and Dorothy Vogel — a postal clerk and a librarian who built one of the most important collections of contemporary art in the country, all while living in a small rent-controlled apartment. They collected with their eyes, not their wallets, forming real relationships with artists long before anyone else cared. The documentary is understated, intimate, and quietly radical: a portrait of collecting as devotion rather than acquisition.

Herb & Dorothy 50x50 (2013)

Directed by Megumi Sasaki

The sequel follows the Vogels’ final, astonishing act of generosity: donating fifty works to a museum in each of the fifty states. The project reveals the depth of their belief in access — that art belongs in public institutions, not private storage. The film becomes a map of generosity itself, tracing how two ordinary people reshaped the cultural landscape of the entire country through small salaries, deep looking, and unwavering commitment.

FROM THE LIBRARY:

DOUBLE VISION: The Unerring Eye of Art World Avatars Dominique and John de Menil

Double Vision: The Unerring Eye of Art World Avatars Dominique and John de Menil, by William Middleton, is a deeply researched dual biography that traces how Dominique de Menil and John de Menil transformed private conviction into public cultural legacy. Drawing on extensive archival material and personal correspondence, the book follows their journey from Europe to Houston and charts the formation of a collecting philosophy grounded in moral seriousness, intellectual rigor, and an unerring trust in artists. Middleton shows how their patronage—shaped by Catholic social thought, political engagement, and an acute sensitivity to form—led to landmark institutions such as the Rothko Chapel, the Menil Collection, and the Cy Twombly Gallery, redefining what it meant for collectors to serve art rather than possess it. More than an account of acquisitions, Double Vision is a portrait of patronage as an ethical practice, revealing how the Menils quietly reshaped the American art landscape by privileging contemplation, access, and responsibility over spectacle or status.

I loved this book. It shows what is possible when people are deeply engaged with art and are willing to share that with the public.

CLOSING THOUGHTS

Art survives because someone gives —

a foundation,

a collector,

an artist,

a neighbor,

a stranger,

someone who believes the work should continue.

Sometimes it’s a fortune.

Sometimes it’s a bag of groceries.

Sometimes it’s a word of encouragement.

All of it counts.

All of it circulates.

All of it keeps the work alive.

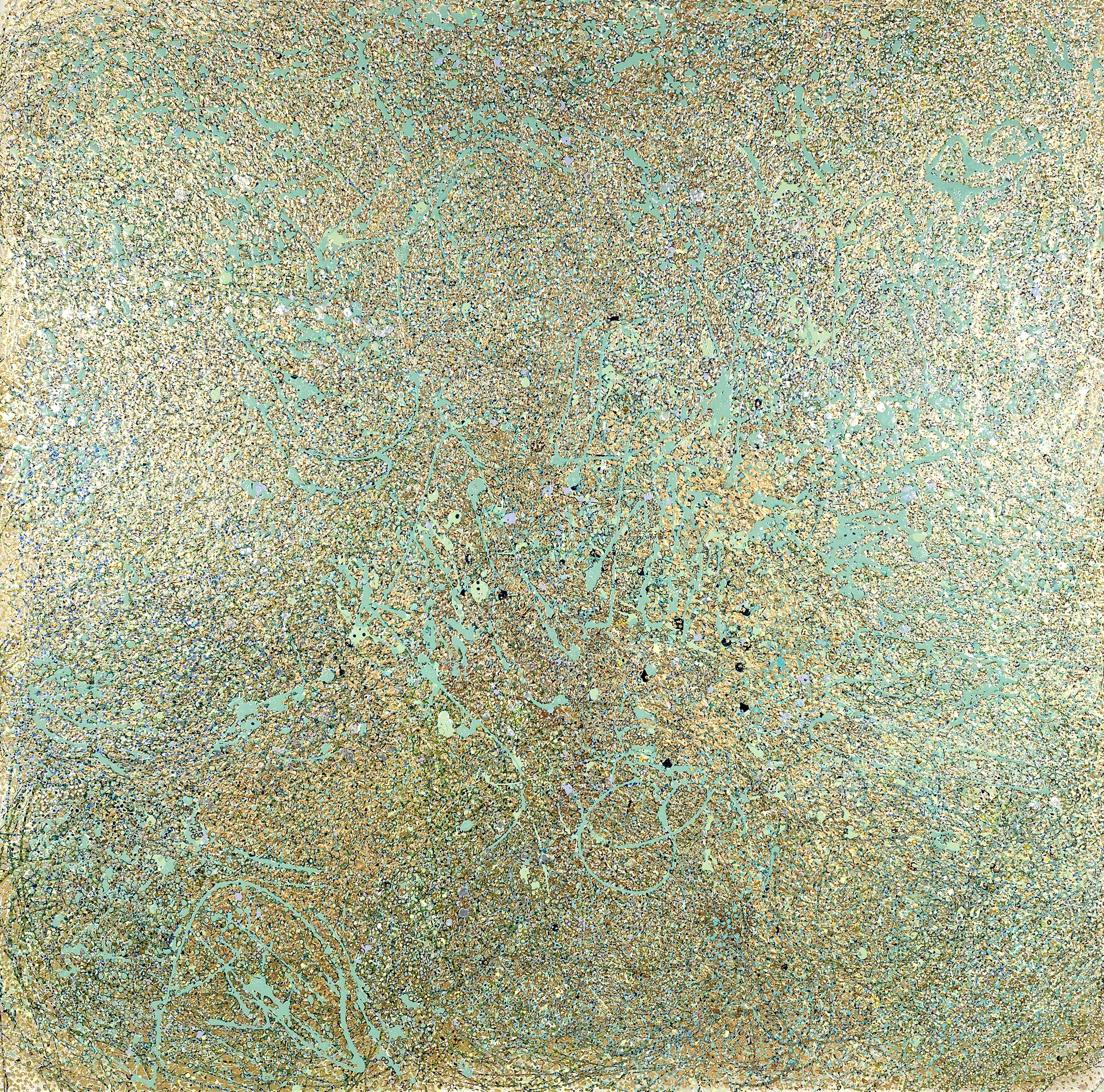

FEATURED ART : RECEIVING

Receiving, 50 inches x 50 inches, oil paint and acrylic markers on canvas, ©2025 Leslie Parke

(Click image for more details)